Fees. Costs. Expenses. Mark-ups. Spreads. Impacts. Sigh. Incentives. Bonuses. Carry. Profits. Awards. Ah yes, friends, the fee machine has been chugging along these past few weeks. What’s new?

In the UK, the financial regulator announced this week that it has evidence that investment advisors are not being clear about fees and, in some cases, purposely misleading clients. In the US, the SEC announced that it found hundreds of private equity firms were inflating fees and expenses to unjustifiable levels. And you can add to this fun mix a renewed belief that financial markets are rigged against average investors. It’s all rather depressing. But please don’t act as if you’re surprised by this.

Oh you thought the cost of borrowing was the same thing as prevailing interest rates? Hilarious. You believed that private equity shops only charged "2 and 20?" How cute. You thought you knew what risks you were paying your investment managers to take? Come on. Better yet, you thought your financial advisors were worth the fees you pay them? Sorry, research now shows that most financial advisors create more damage for their clients than they do value. Even better still, you thought everybody was equal under the law? Ha. Investment professionals seem to steal with impunity.

Sorry, but when exactly are investors going to start standing up for their own interests? How did we even get to this point? How did the financial services industry secure such a dominant position over its customers? I’ve been thinking a lot about this lately, and I’ve got a few ideas:

*Academics: There seems to be a lack of interest in and even respect for the massive principal–agent problems in finance among — wait for it — finance professors. The latter have been overly focused on the challenges shareholders have exerting influence over managers within corporations, but they have largely avoided projects that highlight the huge problems facing investors in disciplining their intermediaries. Why is that?

*Theories: I am of the opinion that investors are too focused on diversification, which — cue financial heresy — is NOT a free lunch. In my view, diversification means that investors focus on the risk and return profiles of financial products — which are structured by intermediaries — instead of developing a view on the underlying assets. This reliance on "products" has helped to create an environment in which intermediaries can overcharge; the layers of complexity make it easy.

*Priorities: Most investors have better things to do than worry too much about how many extra basis points they’re paying to Wall Street. Their focus tends to be on asset allocation, risk management and manager selection — and based on their impact on overall returns, that's probably right. But this means that "cost management" tends to be an afterthought.

*Perspective: It is extremely difficult for single investors, with limited market perspective, to act alone and hope to be successful in keeping costs down. They have a lack of reference to find out the best terms and fees offered by managers. They also tend to be over-confident in their ability to obtain most favored nation terms — which almost all of them don’t.

*Unknown Unknowns: In the world of fees and costs, there are known knowns, such as explicit expenses like management fees. They’re the easiest to reduce, especially if a fund has a good vista of what’s charged in the rest of the market. Then there are the known unknowns, such as implicit expenses like trading spreads or mark-ups. Most investors don’t know that they’re paying them, and because they are often buried in NAV, they can be very tough to uncover. The hardest to deal with, as you might expect, are the unknown unknowns. These are hidden expenses that you don’t realize are even an option ... You can’t reduce these unless you uncover them by knowing where to look. You’d be surprised how many of these exist and are very lucrative.

*Scared Litshess: I’ve come across more institutional investors than I care to discuss that, literally, don’t want to know how much they pay. And they definitely don’t want the world to know how much they pay. Why? Because if they actually got a handle on the delta between their theoretical gross returns and their net returns, they’d have to do something about it. Or they’d be fired.

All of this raises an important question: What can be done to rein in Wall Street? Can anything be done? Perhaps we should just get used to 31-year-olds earning 100s of millions of dollars in a single year thanks to a couple of good trades. Right? Wrong.

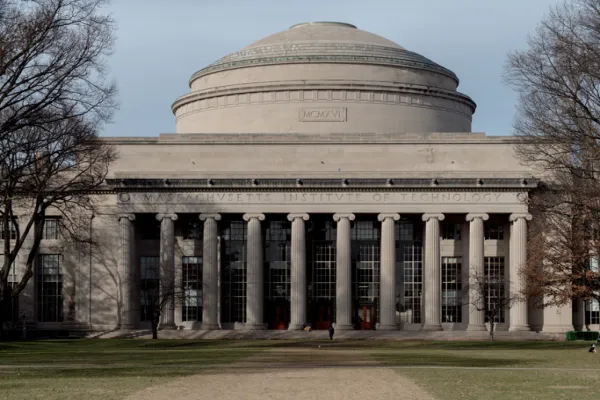

I do see a few solutions, and they largely fit with the core research agendas of my center at Stanford and some of the work I'm doing in the private sector and with the Giants: 1) We need to facilitate the professionalization of institutional investment via good governance; I call this the top-down solution; 2) We then need to nurture highly disruptive technologies that have the potential to disrupt and disintermediate; I call this the bottom-up solution; 3) We then need to reintermediate the industry with new, more-aligned service providers — via seeding managers and encouraging new types of consultants to develop; and, finally, 4) we need to challenge traditional finance theories and models.

It’s a massively daunting project, but I have no illusions. I simply hope that by the end of my professional career, some thirty years from now, I will have seen it completed. As a parting point, I’d like to remind the community of institutional investors that all of this focus on cost is in their interest. After all, investment professionals often forget that an investment in cost and fee reduction provides far greater returns per unit of risk than anything else an investment organization can do ...