It isn’t every day that a country that isn’t broke goes into default. For Argentina, however, that day may be coming soon. With international reserves of nearly $29 billion, Argentina is able and willing to keep up its payments to the investors who bought its sovereign bonds after the country slid into default in 2001 and restructured its debt. Yet a group of holdout investors — led by hedge fund manager Paul Singer — that refused to accept the restructured terms stands to sink the country into default once again.

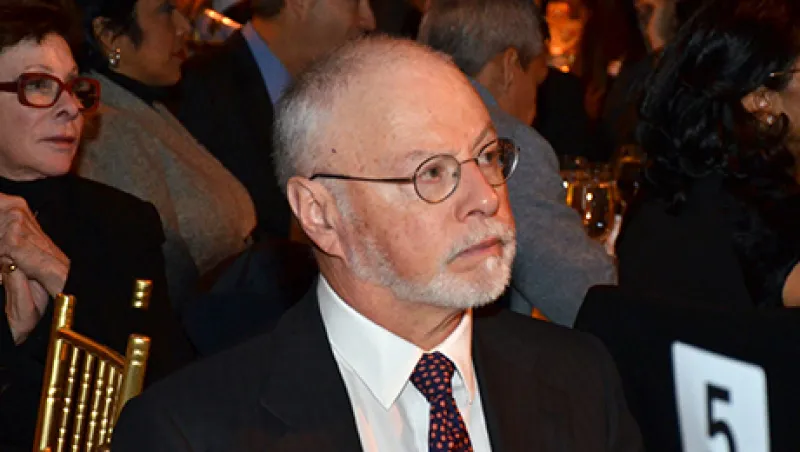

This week a delegation of government officials from Argentina begins discussions with a U.S. court-appointed attorney, Daniel Pollack, in an effort to hammer out an agreement with the holdouts that would keep Argentina from going into default on its sovereign bonds. The creditors who have brought Latin America’s third-largest economy to the brink — known to Argentineans as “the vulture funds” — are being spearheaded by Singer through NML Capital, a subsidiary of his New York–based firm Elliott Management Corp. NML bought Argentinean bonds in 2001. When the country completed its debt restructurings in 2005 and 2010, Singer held out, refusing a payment of 30 cents on the dollar.

In total, 19 creditors held out. Now the group, which also includes hedge fund firm Aurelius Capital Management, is seeking full payment of their bonds for an estimated $1.5 billion. In June the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a lower court order saying that Argentina could not pay off investors in its active bonds — known as the exchange bonds — until it paid off the Singer-led group. The payments to the exchange bondholders were due on Monday, June 30. The money was in the bank, so to speak, but on June 27 U.S. District Judge Thomas Griesa for the Southern District of New York ordered BNY Mellon Corp., which was administering the payment, to return the funds to Argentina until the old bonds were paid off. Argentina has until July 30 to settle with the holdouts before plunging into technical default.

Argentina has its share of economic troubles, including the second-highest inflation rate in Latin America and an overvalued, pegged exchange rate. The country’s populist president, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, hasn’t always pleased Wall Street. Still, its sovereign debt should not be rated distressed, says Marcos Buscaglia, an economist specializing in Latin America at Bank of America Merrill Lynch Global Research in New York. If the country can reach an agreement with its creditors, the sovereign credit rating could increase by at least two notches, he says.

Buscaglia believes the Elliott-led group of creditors needs to be more accommodating. “Judge Griesa is making it a requirement that the participants in the payment process — that is, the creditors — not help Argentina, but Argentina needs help to pay off its creditors,” says Buscaglia.

The problem isn’t paying off the $1.5 billion; Argentina has enough reserves to take care of that. There’s a widespread concern that the courts might force Argentina to also pay off the investors that bought the pre-2001 bonds and agreed to the restructuring terms. Goldman Sachs Group has estimated that the bill to pay off all creditors might be as high as $15 billion: $6.6 billion in defaulted principal, and the rest in past-due interest. That amounts to more than half of Argentina’s international reserves, which, largely because of the overvalued exchange rate over the past few years, have dropped to $28.8 billion, down from $50 billion in 2011, when Kirchner was re-elected president.

One of two things will happen, presumably in the next few weeks during the negotiations between Argentina and the creditors. In the best-case scenario, Argentina and the Singer group will come up with a payment plan. There are ways to do that, even if the country ends up having to foot a $15 billion bill to pay off its restructured debt holders. Daniel Volberg, an economist with Morgan Stanley in New York, suggests in a June report that Argentina might negotiate a bridge loan with international banks. “The upside for Argentina,” Volberg writes, “would be that once holdouts are paid off, the country would regain unfettered access to international capital markets at a fraction of the current double-digit interest rate.” With a low debt load — about 18 percent of gross domestic product, excluding holdings within the public sector — Argentina could tap international markets to bolster its balance sheet, says Volberg.

Moody’s Investors Service rates Argentina’s foreign-currency bonds at Caa1 (stable), the same rating as for Ecuador and Venezuela. Standard & Poor’s and Fitch Ratings have given Argentina negative ratings: CCC- and CC, respectively, the lowest rating of any countries in Latin America. Additionally, S&P put the country on “credit watch negative” on July 1. Buscaglia says the ratings at least partially reflect the credit risks associated with the outcome of the case, but a settlement would change everything. In that scenario, he says, Argentina’s debt ratings should be more in line with Bolivia’s BBB or Paraguay’s BB.

Of course, if Argentina can’t reach a settlement with the holdouts, the country would likely default. Buscaglia says in that case Argentineans would convert pesos into U.S. dollars in droves, and the country’s GDP would fall about 5 percent.

One thing is certain: The October 2015 elections will bring a change in government. Kirchner has served two terms and cannot run for a third consecutive one, and the leading candidates are all running on business-friendly platforms. A new, pro-business government could help foster international confidence in Argentina’s shaky economic footing and thus usher in a gradual recovery.

For her part, Kirchner has been trying to clean up Argentina’s act. One of the reasons courts have been unsympathetic is that Argentina has a record of finding reasons to default on its debt. But in the past year Kirchner has said she is determined to settle with external creditors. She has brought in some price and foreign exchange liberalization and a moderate rise in interest rates, policies that have caused a slowdown in growth but also improved the balance of payments. Kirchner’s efforts reflect a determination to close out her presidency on a high note — more a matter of political legacy rather than an indication of any shift in ideology.

Argentina’s present crisis is good news for new investors looking for bargain prices on sovereign bonds. The implications of the crisis aren’t as pleasant for emerging markets, however. An Argentinean default under the present conditions — a nation that isn’t fundamentally in trouble but might not be able to pay off its debts because of the court-imposed stipulations — might encourage investors in the future to hold out when a country has to restructure its debt. The case brings up a legitimate question: If a country defaults, doesn’t that mean it doesn’t pay its creditors? But the Singer-led group is counting on the courts’ ordering Argentina to pay them off one way or another — and others might expect the same treatment in the future.

Follow Jan Alexander on Twitter at @jananyc.