Alicia Dou recalls how the customer service officer at China Construction Bank repeatedly tried to sell her an investment product whenever she visited her local branch. After being pitched the idea more than ten times, the Beijing-based headhunter finally decided in July 2012 to buy the so-called wealth management product.

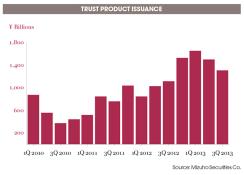

Dou invested 100,000 yuan ($16,500) in a “premium trust certificate” that yielded 12 percent annually, nearly four times the rate the bank pays on one-year term deposits. The certificate, which had a one-year maturity that could be rolled over, was issued through a trust by a group of mining companies from Shanxi, a province southwest of Beijing. Issuance of such trust certificates has soared in recent years, making this one of the fastest-growing areas of China’s so-called shadow banking system, which extends credit outside bank lending channels.

“I took a chance and gained handsomely,” says Dou. Despite the high return, she decided to cash out after one year. “I remember reading the fine print on the certificate: ‘The bank doesn’t guarantee the safety of this investment,’” Dou says. “I asked the teller about it, and she said, ‘Just ignore that: It’s standard contract language. I can tell you our bank will guarantee your money back plus the interest stated on the certificate.’ Though I enjoyed a 12 percent gain, I decided one-year [of] risk was all I was willing to take.”

Dou had reason to be cautious. China’s banks have sold trillions of yuan worth of similar wealth management products in recent years, and those investments are looking increasingly shaky. In January more than 700 investors — both wealthy individuals and institutions such as People’s Insurance Co. (Group) of China, the state-owned company that is the country’s largest property/casualty life insurer — were forced to take an effective write-down on a 3 trillion-yuan certificate, the Credit Equals Gold No. 1 product, after the issuer, mining operator Shanxi Zhengfu Energy Group, ran into financial trouble. Shanxi Zhengfu Energy began defaulting on bank loans and local-investor-backed credit lines last year. To prevent the company from defaulting on the trust certificate — which was issued by China Credit Trust Co., a leading trust company, and sold by Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, the country’s largest bank by assets — the authorities intervened and arranged a deal in which Shanxi Zhengfu Energy paid 2.8 percent interest for the third and final year rather than the product’s supposedly guaranteed 10 percent rate. It was not the first such write-down on a trust product, but it was the most prominent given that the investment had been sold by giant ICBC.

Although the arrangement spared investors larger losses, the opaque nature of the deal failed to reassure some observers. “No one at China Credit Trust, ICBC or the government has announced who ended up paying the bill” on the certificate, says Qian Yanmin, associate professor of finance at Zhejiang University’s College of Economics and a leading expert on China’s shadow banking system. “But there is no question that the government was involved. The mining company, which is going through a debt restructuring, certainly couldn’t afford to pay back the investors. In the end, the government, the trust and perhaps ICBC all played a part in the bailout.”

ICBC declined to comment on the deal to Institutional Investor. Asked about the issue at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, in January, the bank’s chairman, Jiang Jianqing, said ICBC wouldn’t bear responsibility for bailing out investors in wealth products. The incident would serve as a lesson to investors about the risks associated with such investments, he added.

Since 2012 more than 20 trust products totaling 23.8 billion yuan have run into payment difficulties, according to Wang Tao, Hong Kong–based China economist at UBS. About half of those cases are in litigation; the remainder were settled with full or partial payments by the trust companies or their guarantors.

The China Banking Regulatory Commission (CBRC) has begun to strictly monitor the trust industry and will work with individual firms to handle each problem as it occurs, deputy chairman Yang Jiacai said in a recent statement posted on the agency’s website. “Trusts ultimately must take responsibility for any losses incurred,” Yang said, adding that the agency will watch carefully to see that trusts do not use leverage and sell only products backed by capital reserves.

Analysts say the comments by Jiang and Yang suggest that the authorities are worried about the moral hazard of bailouts and do not want to give the market an impression that wealth products have an implicit government guarantee, but that they are also determined to do whatever is needed to safeguard China’s banking system, even if that means selectively bailing out trust products that could pose systemic risks. Some analysts worry that the intervention by the authorities in the case of Credit Equals Gold No. 1 has sent a dangerous signal.

“This is a de facto bailout in our view, and it averted a potentially devastating default risk,” Michael Luk, a Hong Kong–based China economist with Mizuho Securities Co., says of the China Credit Trust incident. “However, it could be negative over the medium term, as investor perceptions of ‘guaranteed principal with 10 percent return’ have been reinforced. Thus it is introducing an even larger moral hazard problem, as it encourages risk-taking behavior.”

Andy Xie, an independent analyst and former chief economist for Morgan Stanley in Asia, has a similar concern. “Investors should be taught a lesson,” he says. “Otherwise China risks systemic crisis further down the road.”

As China’s regulators have clamped down to slow the pace of bank lending in recent years, the country’s shadow banking sector has filled the gap with its own explosive growth. These financial channels have provided a lifeline to private and state-owned companies deprived of credit by the country’s big state-owned banks. They also have given banks high-yielding wealth management products to sell to their customers and allowed banks to sidestep tight controls over deposit rates. Now many analysts worry that the bill for this lending frenzy is coming due.

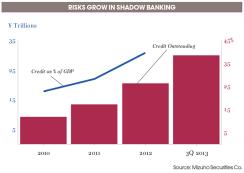

The shadow banking sector had extended more than 30 trillion yuan in credit — that’s $4.9 trillion, or roughly 60 percent of the country’s gross domestic product — as of June 30, 2013, according to various analysts. Trust companies, about a third of the shadow credit market, had sold more than 10 trillion yuan worth of investment products, up from just 2 trillion in 2010; the sector expanded by 40 percent in 2013 alone. The other two thirds of the shadow sector consists of commercial bills, unregulated corporate bonds not underwritten by banks or securities houses, and informal lending channels, including loans made by individuals and companies that borrow from banks or private investment pools and then relend the funds to third parties at higher interest rates. Most of the shadow credit has been extended to private companies and businesses owned by local governments that do not have access to the corporate bond market.

Given the rapid rise in lending, much of it short-term in nature, analysts are growing increasingly concerned about the risk of defaults. Olivier Blanchard, chief economist at the International Monetary Fund, said in January that Chinese authorities need to contain the mounting risks in the financial sector without excessively slowing economic growth. “This is always a very delicate balancing act,” he warned in a conference call with the news media.

The People’s Bank of China has encouraged higher interest rates and even rate volatility over the past year in a bid to slow the growth of shadow banking and encourage greater discipline among lenders — banks and nonbanks alike. Tightening measures were most visible in June, when Chinese interbank lending rates spiked to as high as 28 percent. By September the central bank had drained almost 100 billion yuan from the money markets. Officials allowed a slightly faster appreciation of the renminbi, which rose 3.2 percent against the dollar in the 52 weeks ended February 17.

The measures have had an impact, with growth of the broad money supply, M2, slowing to 13.6 percent year-on-year in December from 14.7 percent in August and growth in total social financing — a broad credit aggregate covering everything from bank lending and shadow credit to bond and equity offerings — easing to 18 percent in December from 20 percent in June. But in its fourth-quarter report, released in mid-January, the central bank continued to express concerns about an “increasing reliance of growth on investment and debt,” citing “massive borrowing and construction led by local governments” and saying that “significant amount of resources went to the property sector, crowding out SME [small and medium-size enterprise] financing.”

The government has the financial resources to contain defaults if they spike. China’s total government debt stood at a manageable 45 percent of GDP at the end of 2012, according to a paper released in January by IMF analysts Sophia Zhang Yuanyan and Steven Barnett. The government owns stakes in state-owned enterprises worth nearly 190 percent of GDP, the analysts note, citing estimates by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, and the authorities control the world’s largest pool of foreign currency reserves: $3.82 trillion at the end of December.

Moreover, big bailouts aren’t new to China. In 1999 the government restructured the four big state-owned banks — ICBC, China Construction Bank Corp., Bank of China and Agricultural Bank of China — by injecting more than $229 billion in fresh capital and moving nonperforming loans off their books. Yet a large-scale bailout of the shadow banking sector would have economic consequences even in China, analysts say.

Liao Qiang, a Beijing-based financial analyst with Standard & Poor’s, believes problems with trust products could damage the banking sector. Already-high debt levels in corporate China leave little room for a further productive rise in leverage given that a significant proportion of shadow banking credit flows to uneconomic investment projects, he says.

“Chinese banks have already accumulated high credit risks on their balance sheets,” says Liao. “But distorted growth in shadow banking could lead to further unintended buildup of credit risks that banks may not fully appreciate. Certain parts of the shadow banking sector, notably trust companies, may prove to be the weak link of China’s financial system.”

The trust and banking sectors are closely interrelated. Trusts have grown largely because of investors’ desire to earn interest rates higher than what Chinese banks are allowed to pay. The central bank has relaxed rules on bank lending rates but still keeps a tight grip on savings rates, setting a ceiling of 3.3 percent on one-year deposits. By comparison, wealth management products in China’s shadow banking sector offer average rates of 5.5 percent, with some exceeding 12 percent, according to analysts at Standard Chartered. Products typically have maturities of one to three years.

Banks have partnered with trust companies to skirt official and self-imposed restrictions on lending. Regulators, for instance, bar banks from lending to industries with overcapacity or to companies owned by local governments. In addition, many private enterprises lack the collateral to obtain bank loans. Banks will often steer such potential borrowers to trusts, which are far less rigorously regulated. And banks help the trusts raise funds by selling certificates of deposit to their wealth management clients.

China’s shadow banking system has a high exposure to real estate and infrastructure industries. Strong growth in those areas has helped drive the economy in recent years, but many analysts believe that the boom has generated lots of bad debt.

Unlike much of the debt that fueled the U.S. housing boom before the financial crisis, however, Chinese wealth management products are not securitized or collateralized, notes UBS’s Wang. As a result, she contends, defaults on trust products should not have a direct impact on the banking sector. But if trust defaults were to occur on a large scale, they could trigger a broader credit crunch in the financial system that would end up hurting the banking sector, Wang says. In such a scenario liquidity would flow back to the banking system, especially large banks, as they have an implicit state guarantee — China’s version of too big to fail, the economist says. However, banks would likely suffer sizable losses in the aftermath as they brought some off-balance-sheet assets back onto their balance sheets and as a credit squeeze slowed the economy and caused nonperforming-loan rates to rise, she adds.

Analysts also note that trust products and other shadow lending vehicles involve a high degree of maturity transformation, financing long-term assets with short-term debt. If rates rise or borrowers have difficulty financing their obligations, the fallout could have wider repercussions in the financial system. Trust-issued wealth management products represent a very small percentage of total assets at the big banks. May Yan, Barclays Capital’s Hong Kong–based financial sector analyst, estimates that the Big Five banks — ICBC, China Construction Bank, Agricultural Bank of China, Bank of China and Bank of Communications — each have an exposure of about 2 percent. The bank with the highest exposure is China Citic Bank, which has sold 412 billion yuan of wealth products, roughly 7 percent of its assets, Yan says. China Minsheng Bank Corp. has the second-highest exposure at roughly 4 percent of assets, he adds.

The government would most likely back up all 10 trillion yuan of trust products sold through Chinese banks, says Zhejiang University’s Qian. “For the sake of protecting the confidence in China’s banking system, the government will step in and protect the interests of those who bought products through the banking system,” he says.

Politically, the trusts are supported by the state, says Andrew Collier, who from 2006 to 2011 served as the New York–based president of Bank of China International’s U.S. operations. “In fact, many of the trusts — as many as 90 percent — are controlled by state-owned or large Chinese corporates,” says Collier, now the managing director of Hong Kong–based Orient Capital Research, an independent financial advisory firm. “These corporates borrow from state banks because they are perceived as a good credit risk and then lend at much higher rates.”

Oil giant PetroChina Co. has various shadow banking units, Collier says. They include an asset management company, a trust bank, a commercial bank and an internal finance unit. Other companies with trust affiliates include Baosteel Group Corp., which owns 98 percent of Fortune Trust & Investment Co., and Yangzijiang Shipbuilding (Holdings), a Singapore-listed company with an 11 billion-yuan trust business that generates more profits than the group’s core shipbuilding business. “Given that many trusts are state-owned or connected to state banks, the backing by state entities is high, and the risks of default are lower,” Collier says.

The central government will be far less inclined to guarantee the other two thirds of shadow banking, analysts say. These credits have been extended by individuals, companies, guarantee firms and private equity houses, among other entities. According to Qian, they include 16 trillion yuan of loans to private and local-government-owned companies, the vast majority of which ended up in real estate and infrastructure, and 4 trillion yuan in loans to private asset management houses, which used the proceeds for a wide range of investments, including long-only equity and hedge funds.

According to a recent report by China’s National Audit Office, local governments owe a total of 17.9 trillion yuan, much of it borrowed by local-government-owned companies for infrastructure development.

Shadow banking rose in China on the back of the government’s 4 trillion-yuan fiscal stimulus, unleashed in 2009 to sustain growth at a time when the fallout from the collapse of Lehman Brothers Holdings was spreading recession around the world. Worried about the impact of the global slowdown on China’s export industries, officials in Beijing openly encouraged local governments and the private sector to begin a spending spree on infrastructure — everything from highways and mass transportation systems to power plants and water treatment plants. The money also flowed to commodity and construction material producers participating in China’s massive urbanization program, which aims to accommodate the 230 million rural residents expected to move into urban areas over the next two decades.

“The problem is, many of these projects cannot generate cash flow or take years to achieve low operational profitability,” says Zhejiang University’s Qian. In more-developed nations, companies — whether private or local-government-owned — finance such projects by issuing low-interest-rate bonds that mature in five to 20 years or more, he says. In China, however, the bond market is still in its infancy. Beijing has allowed only a few select cities and provinces to experiment with municipal bond issues.

China’s bond market, though the fourth largest in the world, with more than $3.4 trillion in issues outstanding at the end of 2013, is still highly restrictive as to what kinds of companies can issue debt. The authorities extend preferential treatment to the Ministry of Finance, policy banks and enterprises that are owned by the central government, excluding private enterprises and those owned by local governments.

“As a result, most of the private and local-government-owned companies with capital needs went to trust companies or other informal lenders to raise funding,” says Qian. “That is why you have many local infrastructure companies sitting on a pile of short-term debt that requires them to pay interest rates that are as high as three times what a bank would charge.”

Debt owed by local-government-owned companies carries less risk than the debt of private sector companies, Qian explains. “Most local governments still own substantial assets, which they can sell to avoid defaulting on debt owed by their investment companies,” he says. “It’s another story with private companies, however.”

Because of a lack of sophisticated credit analysis of trust products and fundraising vehicles owned by local governments, no one quite knows the severity of the crisis that may come, not even the Chinese government, which is still working on a comprehensive solution, Qian says. “The central government is focused on regulatory oversight and dealing with the defaults as they come,” he notes. “Most importantly, Premier Li Keqiang wants to send a message to the marketplace: Don’t count on the government to bail you out. Investor must beware — only when there is high risk will there be high returns.”

There has been tremendous internal debate about the matter. Some senior officials advocate letting the bad loans default without any official intervention, whereas others think the authorities should manage the process with selective bailouts, says Orient Capital Research’s Collier.

“The outcome of the ICBC case was confusing even in China,” he explains. “The head of treasury operations for a Chinese commercial bank in Beijing last week texted me, ‘This may be the first trust default.’ In contrast, a policy analyst for the PBOC told me, ‘I don’t think the central government could let it default.’ However, he added, ‘If the default can be controlled and orderly, the result would be better.’”

The government has been grappling with an appropriate regulatory framework for shadow banking for some time now. In 2010 the CBRC began requiring China’s 65 trust companies to carry capital against their assets under management. As of September 2013 the trusts collectively had 10 trillion yuan in capital, according to the China Trustee Association, an industry group that acts as an intermediary between regulators and the country’s trust companies. China’s trust industry is still far smaller than the banking industry, which had 128.5 trillion yuan in assets as of September 2013, but according to a Barclays researcher, the sector is already bigger than China’s insurance industry, which has 8.1 trillion yuan in assets.

To help address what may be a massive cleanup of China’s shadow banking sector and to head off a financial crisis, China’s State Council — the nation’s cabinet — has announced that it will begin reining in trusts and other informal lenders and tighten regulations on them. Released in January, Document No. 107 of the State Council aims to classify and regulate the shadow banking business. The document is short on details but is intended to provide the foundation for a shadow banking law that will be written during the National People’s Congress, to be held in Beijing this month.

The law will provide clear regulatory oversight of all types of financial intermediation outside China’s traditional banking, securities and asset management channels. Rather than killing off shadow banking, the document indicates that the sector is an inevitable result of financial development and innovation and broadens the investment options available to the Chinese people, says Barclays Capital’s Yan. “We believe that tougher rules on shadow banking could trigger some negative effects on China’s overall economy and financial system,” she says. “However, we believe the regulators are likely to balance economic growth against the risks of a slowdown of shadow banking. We believe strengthening regulation on shadow banking is necessary for the healthy development of the financial system in the long run.”

The regulatory move by authorities coincided with a shutdown of various informal lenders around the country. In January officials forced the closing of three unauthorized, Internet-based peer-to-peer lenders that were doing brisk business: Hangzhou Guolin Chuangtou Co., Shanghai Fengyi Xintou Co. and Shenzhen Zhongdai Xinchuang Co. Authorities are seeking the owner of the three outfits, Zhen Xudong, but haven’t charged him with any crime.

Officials in recent months also have shut down more than 1,000 illegal lenders that styled themselves as private equity firms. The firms borrowed funds from banks at rates of 5 to 6 percent and then lent the money to third parties, mainly private companies, at rates as high as 20 percent a year.

“These guys were loan-sharking,” says Li Zhiyong, the Beijing-based deputy chairman of the China Venture Capital and Private Equity Association, which is working with authorities to quash illegal activities in the private equity industry. “China’s financial sector still isn’t well regulated,” Li says. “But once regulators discover illegal activities, they will crack down.”

The official clampdown coincides with a recognition that defaults will rise in the months ahead. According to Zhang Zhiwei, chief China economist at Nomura Securities in Hong Kong, roughly 3.5 trillion yuan of trust products will mature this year.

“We maintain our view that credit defaults will happen in the corporate, local government financing vehicle and shadow banking sectors, such as trust companies themselves, in 2014,” Zhang says. The economy is slowing, and interest rates are rising, putting financial pressure on all those entities, he notes. In addition, some local governments will face fiscal pressures in 2014 as property-related taxes and land sales, which swelled local government coffers in 2013, slow down, he contends.

How will the government handle bad debts in the shadow banking sector? One possible example came last May, when Citic Trust Co., a unit of Citic Group Corp. and the country’s largest trust company, auctioned off 1.3 billion yuan in high-interest loans to a steel plate manufacturer in Hubei province in central China. Citic Trust never disclosed the buyer’s identity but said all wealthy investors who had purchased the trust product, which paid annual interest of 10 percent, would be paid in full; according to Chinese media, they were paid.

“The administration of President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Keqiang wants to use market mechanisms to resolve this crisis,” says Guan Anping, a Beijing-based securities lawyer and government adviser. “That means they will allow defaults and also allow investors — both domestic and foreign — to participate in acquiring the distressed assets.”

The authorities are also likely to turn to distressed-debt investors, who played a role in the workout of bad loans in the banking system more than a decade ago. It’s instructive that China Cinda Asset Management Co., the country’s leading distressed-asset manager, was able to raise $2.5 billion in an initial public offering in December, the largest IPO in Hong Kong last year.

Cinda was set up in 1999 for the express purpose of taking over and processing more than $30 billion of bad debt from China Construction Bank, the nation’s second-largest lender, and China Development Bank. Over the years Cinda has earned money by restructuring nonperforming loans and selling them off to other investors. The company reported a 36 percent rise in profits attributable to equity holders in the first half of 2013, to 4.06 billion yuan.

“It has several cash-generating businesses besides asset disposals,” says Paul Schulte, a former analyst with CCB International (Holdings) who is now CEO of his own Hong Kong–based analytical firm, Schulte-Research. “So it provides good cash and has a good degree of control over assets.” Schulte believes Cinda may buy as much as 100 billion yuan of additional distressed assets in the coming two years to begin the debt restructuring cycle again.

A group of global institutional investors — including Norway’s sovereign wealth fund and New York–based hedge fund firm Och-Ziff Capital Management Group — has bought about $1.1 billion of Cinda’s stock as cornerstone investors. China Huarong Asset Management Corp., another leading debt collector, is in the process of preparing for an IPO and hopes to raise as much as $2 billion, sources say. Distressed-debt collectors China Orient Asset Management Corp. and China Great Wall Asset Management Corp. also are preparing for offshore listings.

China has plenty of experience in restructuring bad debt. The bank restructuring begun back in 1999 removed hundreds of billions of dollars worth of bad loans from the system and recapitalized the Big Four banks, allowing them to go public with record-breaking IPOs less than a decade later. The question is whether the government can successfully tackle shadow banking problems in the same way today.

Jun Ma, chief China economist at Deutsche Bank, thinks the authorities can pull it off. “China’s financial risks are being addressed by reforms,” he says. “Many investors fear that China’s wealth management product defaults and local government finance vehicle loans will lead to a blowup of the financial system. This is very unlikely in our view.” The recent resolution of the China Credit Trust product indicates that the authorities are embarking on a path toward “managed defaults” to gradually improve risk pricing in the trust loan sector, Ma says. Meanwhile, they are tightening rules on shadow banking activities, such as centralizing wealth management operations in banks’ headquarters and increasing supervision of trust companies.

Local-government-owned finance vehicles saw their leverage ratios decline in the past two and a half years by an average of 4.9 percentage points, Ma says, citing a recent National Audit Office report. “The local government bond market will be developed to gradually replace local government vehicle loans as a more important source of financing for local government capital expenditure,” he says. Beijing may also expand municipal bond market experiments launched in 2010 in the cities of Shanghai and Shenzhen and the provinces of Guangdong and Zhejiang. “These reforms should reduce financial risks rather than increase risks,” Ma contends.

That would be a welcome trend. The health of the Chinese economy — and those of many emerging-markets countries that rely on exports to China — will depend heavily on whether the government can contain risks in the shadow banking sector and turn today’s problem debts into profit-making opportunities. Investors around the world will be watching eagerly to see if policymakers in Beijing can succeed. • •

Follow Allen T. Cheng on Twitter at @acheng87.