Yesterday I examined the possibility that unprecedented injections of liquidity by the Federal Reserve Board and other leading central banks had suppressed normal market volatility, potentially storing up bigger risks in the future (see “How Low Can Volatility Go? Why Tranquility Keeps Traders Awake at Night”).

Liquidity may not be the whole story, though. A group of global macro traders that I gathered recently at Oxfordshire’s Ditchley Park estate to assess the outlook cited three other potential explanations for the extraordinarily low level of volatility in financial markets: a reduction in systemic risk as a result of postcrisis financial regulation and deleveraging, a sweet spot in the global economic cycle that is typically marked by low volatility, and a lack of geopolitical tensions to rile markets. These aren’t necessarily separate risks. In fact, they can amplify and interact with the tightening of central bank liquidity. Let’s examine these hypotheses in turn.

Systemic Risk Has Been Drained

There are three possible sources of systemic risk: the untested plumbing of the financial system, persistent high leverage and old-fashioned regional economic crises, akin to the one we have seen intermittently in the euro zone over the past five years — and ones we may well see in emerging markets over the next five.“Our research suggests that the true underlying risk to portfolios is not accurately reflected in the implied market volatility indices,” said Mark Farrington, head of London-based Macro Currency Group, when I quizzed him on vol exactly a year ago. Surveying the steady implosion of volatility since then, he still believes systemic risk is being underpriced.

“If deleveraging at financial institutions was the petrol that fueled the fire of the global financial crisis volatility, the next crisis will draw fuel from insufficient secondary market liquidity to facilitate the real money position adjustment that will come with the start of Fed tightening,” says Farrington now. “A big vol event is coming, but its violence will be driven by poor market liquidity, not deleveraging. The Dodd-Frank regs and downsizing by banks have dangerously debased market-making balance sheets. In spite of politicians’ wanting fewer ‘too big to fail’ banks, the global markets keep growing in size, and we need even larger financial institutions to handle the secondary liquidity needs.”

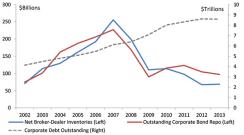

Consistent with this view, the Financial Times ran an alarming headline about the risk of a run on bond funds in its June 16 edition, suggesting that all that has been drained from the international financial system is liquidity, not risk. “In the wake of the financial crisis, tougher rules on capital and the abolition of in-house trading operations at major U.S. banks have resulted in Wall Street pulling back from helping big funds buy and sell corporate bonds,” the article claimed. “Bank inventories of bonds have fallen almost three-quarters from their pre-crisis peak of $235 billion, according to Fed data. At the same time, U.S. retail investors have pumped more than $1 trillion into bond funds since early 2009. This has created a boom environment for fixed income money managers, but raises the prospect of a massive disorganized flight of money out of the industry should interest rates rise sharply in the coming years.”

Incidentally, this type of flight by unlevered investors was cited as one of several possible triggers for a sharp decline in the markets by JPMorgan Chase & Co. chief U.S. economist Michael Feroli and his co-authors in their recent paper, “Market Tantrums and Monetary Policy.”

Liquidity Ebbs Away

|

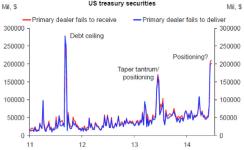

Canny traders and analysts are already looking for early warning signs that tapering might stress the plumbing of the financial markets. “Where should we expect to see signs of stresses in the financial system when the Fed exits with a big balance sheet?” asks Torsten Slok, chief international economist at Deutsche Bank Securities. “One small sign of stress more recently is the spike we have seen in the number of fails.” (In Wall Street argot, a “fail” occurs when securities in a buy or sell transaction aren’t delivered by the settlement date, which often happens when traders put on a so-called naked short — selling a security short without any means of buying it back.) “If this is a reflection of lack of high-quality collateral to support a significant amount of shorts in the front end and belly of the curve, then I worry what could happen as we get closer to the Fed exit and even more investors want to be short rates.”

A Rising Tide of Treasury Fails

|

| Source: FRBNY, Haver Analytics, DB Global Markets Research |

As for the sustained leverage story, “The headline number out of the BIS is that nonfinancial public plus private debt is 20 percent larger than it was in 2007. So, on a global basis, there has been no deleveraging,” says William White, chairman of the Economic Development and Review Committee at the OECD in Paris and a former chief economist at the Bank for International Settlements, whose former colleagues at the Basel-based institution continue to track this carefully. “Public debt has increased because of the action of normal countercyclical policy through automatic stabilizers. However, the big problem has been that private sector debt, with the important exception of the U.S., has not gone down. The developed markets have reached 100 percent debt-to-GDP levels, which are well above a reasonable comfort zone, especially in Europe.”

How about an old-fashioned balance of payments and currency crisis, either within the euro zone periphery or by an emerging-markets sovereign?

Despite the failure of Europe (ex-U.K.) to delever, a semiannual poll of global macro traders that I conduct for Institutional Investor continues to assign a shrinking probability of default by any euro zone periphery state. In June just 1 out of 10 respondents thought there would be a euro zone default by the end of 2014, down from 13 percent in December 2013. Interesting, they also foresee only a 1 in 3 chance that the European Central Bank will begin its own version of quantitative expansion before the year is out.

“Courtesy of [president] Mario Draghi, the ECB’s intervention has been effective in addressing the stability of the banking system,” agrees Michael Hintze, founder and CEO of CQS. “One could argue that there was a significant amount of ‘kicking the can down the road.’ This breathing space, together with the markets’ faith in Draghi, has enabled banks to supplement their reserves through retained earnings as well as through issuance of equity and tier-1 debt to strengthen their capital structures. Capital ratios are stronger; inflation of asset prices, thanks to the liquidity created by central banks, has reduced the probability of default.”

Several of the Ditchley participants thought that there was still ample trouble brewing in emerging markets, which could lead to episodic volatility in foreign exchange markets and EM sovereign debt markets, with several candidates in the wings beyond the so-called Fragile Five of Brazil, India, Indonesia, South Africa and Turkey. “The EM countries have undergone enormous credit expansion,” says White. “Significant amounts of foreign currency and especially dollar-denominated debt are laying the structural groundwork for the same kind of problems that caused the 1990s Asian financial crisis.”

This is the “déjà vu all over again” story, expressed elegantly by Michael Pettis in his dissection of the Asian financial crisis in the book The Volatility Machine, echoing the late economist Hyman Minsky’s classic argument that long periods of stability are ultimately destabilizing. “Risky structures are usually built up by risky financial practices during periods of financial tranquility,” writes Pettis, a senior associate at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace’s Asia Program in Beijing. “As asset prices rise and expected returns on safe assets decline, investors begin to widen their horizons in search of higher returns — they become ‘yield hogs,’ in Wall Street lingo.”

Then comes an exogenous shock. What determines whether the shock becomes an irritant or a calamity? “The virulence of the crisis is largely a factor of capital structure vulnerability,” writes Pettis. High levels of foreign currency debt by many EM countries, both corporates and sovereigns, keep that vulnerability high — if and when the shock occurs. The sharper the devaluation of a country’s currency in a crisis, the higher the foreign currency debt burden becomes.

Our traders’ survey forecasts an average 30 percent probability of a balance of payments crisis this year in one or more of the Fragile Five, with South Africa and Turkey the most vulnerable. This is down from a 43 percent probability assessed in December 2013. The traders perceive both Brazil and India as being largely out of the woods, at least for the rest of this year.

The continuing miners’ strike in South Africa and the nasty infighting between Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s ruling Justice and Development Party and the Gulenists in Turkey kept those countries at the top of the Fragile Five list. In contrast, the absence of social strife around the World Cup in Brazil and the landslide election victory of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party in India dispelled some of the perceived risk of a crisis in those nations.

So could systemic risk rise up again and trigger a revival of vol? Perhaps, but the potential appears less acute today than in the past. No one really knows about the hidden pressures inside the financial plumbing, leverage hasn’t declined outside the U.S., and the currency crisis potential is down in both Europe and most emerging markets.

Macroeconomic Cycle

The most conventional explanation of the moderation of volatility is the macroeconomic cycle. Volatility is always lower in the early phases of a recovery. According to Charles Himmelberg, head of global credit strategy at Goldman Sachs Group, “The most important empirical predictor of asset volatility is the phase of the business cycle.”“Nothing has happened with U.S. equity volatility that suggests the lull since January 2013 is anything other than cyclical,” agrees Jim Strugger, equity derivatives strategist at MKM Partners, a Stamford, Connecticut–based brokerage. “That the recent trough has stretched on since April, far surpassing other episodes of suppressed volatility over the past 18 months, does suggest an increase in equity market instability. But any risk event in the context of this low-volatility regime would likely be within the magnitude range of others over this period.”

Volatility could return if this cycle takes a significantly different trajectory than previous ones. The U.S. recovery has been more sluggish than most postwar rebounds, for example, and emerging markets have played a much larger role as an engine of growth. China accounted for the lion’s share of global growth over the past five years. How could this change going forward?

The traders’ poll assigned an average 56 percent probability that China’s gross domestic product will fall below the government’s 7 percent growth target this year. (The survey took place before Beijing’s July 16 announcement that the year-on-year growth rate edged up to 7.5 percent in the second quarter.) This is slightly more pessimistic than the December 2013 bet, and traders surveyed expressed widespread skepticism about the quality of official statistics coming out of Beijing, and even deeper fears that a credit bubble in China’s shadow banking system could burst.

“While it appears that China’s shadow banking is a self-contained issue, it is not,” warns CQS’s Hintze. “Much of the financing of the carry trades comes via international banks outside China. This creates the linkage internationally. Simplistically, money is borrowed offshore China and invested onshore in China trust funds, and the carry differential is significant. The linkage of trust funds to the international financial system creates contagion risk, and that’s not in the price. The good news is that the Chinese leadership is aware; they are capable. If Draghi can kick the can down the road in the euro zone, so can the Chinese.”

“A genuine economic crisis could erupt completely independently of what the official Chinese GDP number is doing,” says Leland Miller, a Ditchley participant and president of China Beige Book International, which independently constructs economic data series for the People’s Republic. “There could be a major problem with the shadow banking system without the official GDP number moving at all. The chance of seeing an official hard landing, where reported GDP growth drops off a cliff, is extremely low. The idea that the Chinese will announce a growth number outside of their targeted band is very low.”

“Every economic statistic I look at in China indicates the country is in a deep recession,” argues a New York–based macro trader. “Their leadership is focused on corruption and the environment, and both efforts are very negative for growth in the short term. When you start focusing on corruption, decision making completely freezes up.”

“Capex fell dramatically the second quarter of 2014, far and away the largest drop and lowest overall level that we’ve seen in three years,” observes Miller. “The next inevitable puffed-up official GDP figures aside, the data suggest that the Chinese may finally be internalizing that the current slowdown is a permanent one and reacting by both borrowing and spending less.”

We Live in a Safer World (Not)

A fourth explanation for the decline of volatility contends that we are living in a safer world. And in our June poll, traders offered an across-the-board lower assessment that any of the security threats we usually track will take place this year. They estimate the probability of a major maritime clash between China and Japan, or between China and countries in Southeast Asia, at only 19 percent, down slightly from 20 percent in December 2013. Similarly, they put the risk of a strike on Iranian nuclear facilities at just 11 percent, down from 18 percent previously, and they dramatically lower the odds of major social unrest in an EU periphery state, to 16 percent from 37 percent.The major exception to a quieter, safer world is the price of oil. Our traders’ poll assigned a 53 percent probability that North Sea Brent crude will stay within a band of $100 and $120 per barrel in the second half of this year, with a one-third chance that it will trade above $120 by December 31. Reflecting a pessimistic assessment of Middle Eastern supply shocks, notably in Iraq and Libya, they say it’s just a 16 percent bet that Brent will fall below $100; in December 2013, they had put those odds at 34 percent.

“From a demand standpoint, Western European and North American growth in energy demand has slowed down significantly,” says a New York–based macro trader. “China has gone from 9 percent to 11 percent of the world’s consumption; other Asia, from 11 percent to 13 percent; and the Arab world, from 7 percent to 9 percent. But the interesting point is that China is currently shrinking in terms of its proportion of world demand. For the first time ever, China’s oil demand growth has gone negative. This is the first time we’ve ever seen this.” This view is consistent with the June poll’s skeptical view of Chinese GDP growth.

“The price of oil has been remarkably flat for three years with no volatility,” mused another macro trader with long experience in energy markets. “Over the last year enormous geopolitical risks have emerged, especially Libya, which seems to be on the verge of civil war and of producing no oil. We have lost hundreds of thousands of barrels per day of production over the last nine months, yet what has happened to oil price? Absolutely nothing.”

He continued, with some conviction, “I strongly believe that the geopolitical risks are the highest I’ve seen in my career. There is a good chance Libya never comes back online. Iran is in trouble. The market is counting on Iraq to raise production, but the country could fall apart at any time. Inventories are at record lows, but prices continue to do nothing. In the context of the oil market, this does not make sense. My strongest view on the oil market is that this low-volatility environment cannot persist. If something happens in Iran or Russia or Iraq, prices will spike very high, very quickly.”

In contrast to the across-the-board assessment of lower security risks, the June poll revealed a pessimistic assessment of three hot spots: a one-third risk of major violence (defined as more than 1,000 deaths) in Egypt and Ukraine this year, and a 58 percent probability that Iraq will dissolve into full-scale civil war.

The Sunni militant organization ISIS surprised a lot of observers by the speed with which it swept down the Land Between the Rivers, threatening even Baghdad. I confess that I was stunned to see ISIS parading a Scud missile in Raqqa (in Syria) on July 2, and then watch Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, self-proclaimed caliph of ISIS, give a riveting 15-minute public speech in the Great Mosque in Mosul on July 5. It is hard to imagine Taliban head Mullah Omar making a public appearance like that without having to duck a couple of drone strikes.

“ISIS is likely to continue to absorb other radical factions operating in Syria and Iraq, such as the Jabhat al-Nusra and other offshoots of the al-Qaeda network,” warns Crispin Hawes, Middle East expert and managing director of Teneo Intelligence in London. “If ISIS is allowed to expand, reinforced by the capture of weapons and money in Iraq, it will come to pose a direct threat to states that are not, as Iraq was, intrinsically vulnerable. This is a nightmare scenario for a number of states in the region, but particularly Jordan, Lebanon and Saudi Arabia, which are potentially immediate targets for ISIS. It is perhaps already possible that the jihadi-controlled areas of Syria and Iraq will remain outside the control of any government in the region for several years.”

The sudden appearance of an Islamic terrorist state in parts of Iraq and Syria apparently came as much of a surprise to the Obama administration as it did to Wall Street, given officials’ frequent claims that al-Qaeda was on the ropes. Jeh Johnson, secretary of Homeland Security, publicly boasted in November 2012 that “the core of al-Qaeda is today degraded, disorganized and on the run. Osama bin Laden is dead. Many other leaders and terrorist operatives of al-Qaeda are dead or captured; those left in al-Qaeda’s core struggle to communicate, issue orders and recruit.” It looks as if Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi didn’t get that memo. But even this unpleasant surprise didn’t seem to move markets; The VIX moderation continues apace.

I am puzzled by the mean predictions of continued low volatility by the same traders who assign an average 58 percent probability that Ukraine will descend into civil war. So far, they seem right about the mounting violence. In recent days, Ukrainian military aircraft and the tragic Malaysian Airlines Flight MH17 have been shot down over eastern Ukraine, apparently by separatist forces armed with Russian missiles, while the Ukrainian army has been getting ready for a Fallujah-like assault on Donetsk.

Some believe that economic self-interest will limit the escalation of pressure on President Vladimir Putin. “The Europeans are acutely aware of the potential financial ramifications of sanctions and the possible spillover effects on their banking system,” said a New York–based global macro trader at Ditchley Park. “Sanctions on Iran and Syria are easy for them to support. With all the Russian debt held by European institutions, as well as their dependence on Russian gas, it is much more difficult for the Europeans to contemplate entering into a spiral of sanctions and countersanctions with Moscow.” But with wreckage and bodies from MH17 strewn over the fields near Donetsk and the Obama administration clearly blaming pro-Russia separatists, European reluctance to tighten sanctions on the Kremlin is likely to face a stiff test.

“The recent downshift in equity volatility is indicative of complacency becoming evenly more deeply imbedded,” cautions MKM’s Strugger. “Our recommendation is to exploit the low level of implied volatility to actively maintain appropriate hedges. The risk of this environment is that investors become smug to the point of leaving portfolios defenseless and vulnerable to the inevitable lift in volatility.”

Bhanu Baweja, head of emerging-markets fixed income and currency strategy at UBS, agrees: “It’s difficult to forecast the exact date and time of a serious spike in volatility. Volatility has certainly remained low for long periods historically, and low volatility hasn’t necessarily foreshadowed a big move lower in asset prices. However, the variables that are driving low volatility today — ultraloose monetary policy, weak secondary market volumes, a strong certainty around decent earnings amidst ‘muddle through’ growth — don’t seem to us as reliable fixtures for anything beyond the very short term.”

James Shinn is a lecturer at Princeton University’s School of Engineering and Applied Science (jshinn@princeton.edu) and CEO of Teneo Intelligence. After careers on Wall Street and Silicon Valley, he served as national intelligence officer for East Asia at the Central Intelligence Agency and as assistant secretary of defense for Asia at the Pentagon. He sits on the advisory boards of Kensho, a Cambridge, Massachusetts–based data analytics firm, and CQS, a London-based hedge fund.