Despite resistance from Germany, as well as some of the social stigma associated with sovereign quantitative easing’s being a rich man’s game, we think that by the second quarter of 2015, the European Central Bank will be forced to do QE to overcome not only the ongoing deflation threat but also the physical reality that it is difficult to fulfill its pledge of €1 trillion ($1.22 trillion) in asset growth without expanding beyond credit markets.

Foreign investors have fled Europe in favor of dollar-based equities. In prior years investor sentiment was more positive toward Europe, Latin America and Asia than it was toward the U.S. In 2014 investors have practically put the U.S. on a pedestal. We don’t disagree with the macro view that the U.S. is probably best positioned among the regional economies that we cover. Everything has a price, however, particularly when growth in gross domestic product does not equal corporate growth. Case in point: Consider that China’s GDP this year will grow 7 percent, but Chinese companies’ earnings per share will only increase 3 percent.

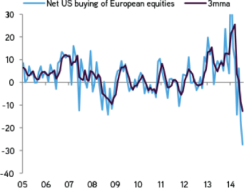

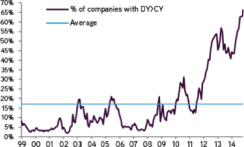

So whereas we fully acknowledge that Europe faces headwinds, there are two things that make us at KKR think value buyers and contrarians should find the Continent an at least somewhat intriguing prospect. First, extreme selling by U.S. investors of European stocks reached a level in October 2014 that we have not seen since the 2008–’09 financial crisis. Apparently, the International Monetary Fund’s disclosure in October that Europe has some structural issues came as news to many folks in the investment community. Second, we find it interesting that 65 percent of European stocks now have a dividend yield above their corporate bond yield. This mismatch occurred in the U.S. in 2010–’11, and it represented an important signal that there was value in the market (see chart 1).

Selling by U.S. Investors Has Been Similar to 2008–’09

Data as of November 14. Source: U.S. Treasury, Haver Analytics, Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research

A Record Number of Companies Now Have Dividend Yields Above Corporate Bond Yields

Data as of October 21. Source: Datastream, Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research

In our view, the marginal-change thesis remains intact, but the disinflation cycle must be arrested to inspire more nominal revenue growth and valuation support. Against the macro backdrop, we continue to focus on countries and sectors in which there is positive macro momentum. Reformist countries like Ireland, which in our view will likely grow 5 percent in real terms in 2014, and Spain continue to deliver upside surprises, a trend we expect to continue. We also remain constructive on the Nordic region and the U.K., and we have even heard of a growing number of companies reinvesting in some countries in peripheral Europe as conditions improve. By comparison, we left this trip to Europe with even more concerns over the outlook for Italy and France.

We also think it makes sense to appreciate what the current macro landscape means for sectors and companies. Given the macro backdrop we see for Europe over the next few years, we continue to believe that, all else being equal, we should continue to avoid companies linked to government spending and/or traditional consumption on the Continent. Wage degradation and government belt tightening are now structural, not cyclical, forces at work.

By contrast, we think the consumer trade-down thesis is alive and well, a theme we heard confirmed by several executives. We also continue to find solid European companies poised to either consolidate a sector or take their business global. Within technology, substitution remains a compelling theme across media and business services. Lastly, bank deleveraging also remains an important theme. Overall, though, we believe all of Europe needs to do more to address mounting deflation and growth pressures. History shows that taming inflation is often easier than quelling deflation.

Improvement requires monetary and fiscal initiatives at the federal level, and for France and Italy to follow some lessons learned in countries like Ireland and Spain.

Ultimately, before the next downturn, the region needs to do more to get nominal GDP above nominal interest rates. Otherwise, when we do enter a downturn, government debt levels in areas like France and Italy will move from outsize to unsustainable, which will put undue pressure on the European Union. And unlike Greece or Cyprus, the stakes are much higher, given the sheer size of debt outstanding in Italy and the two countries’ contribution to European GDP.

Henry McVey is the head of global macro and asset allocation at KKR in New York.

Get more on macro.