Since the 2008–’09 financial crisis, government policy and direct issuance of Treasuries have resulted in increased duration and lower yields in the Barclays U.S. Aggregate index, also known as the “Agg.” These changes pose a direct challenge to investors in bond index funds, which are fully exposed to the concentrated risks now embedded in the index. Unlike index funds, actively managed funds seek to mitigate concentrated or poorly compensated risks while identifying pockets of value across the broad bond markets. We believe that modest return expectations and the prospect for higher interest rates favor active management, which provides investors an opportunity to retain the benefits of core bonds while potentially mitigating risk and earning higher returns.

Investors typically rely on core fixed income to dampen volatility and generate a high-quality source of return in portfolios. The combination of duration and yield in a core bond portfolio generally functions as the primary diversifier to equity exposure.

We expect core bonds to continue to play a key role in portfolio risk management and asset allocation. The Barclays U.S. Aggregate index represents the attributes sought by core bond investors: intermediate-duration, high-quality U.S. fixed income.

Policy responses to the financial crisis, however, have altered the risk characteristics of the Agg. Investors who have not revisited the index recently might be surprised at the extent of the changes.

Duration on the U.S. Aggregate increased from 3.7 years at year-end 2008, at the peak of the financial crisis, to 5.6 years at present (see chart 1). Yield-to-maturity fell from 4 percent at the end of 2008 to 2.2 now, nearly the end of 2014. What this means for investors is that the yield per unit of duration has decreased from 1.1 to 0.4 over the past six years. So using a core bond index fund today exposes portfolios to greater interest rate risk with limited compensation in the form of yield.

Barclays U.S. Aggregate Index: Duration Has Increased While Yields Have Fallen

The U.S. Aggregate is the most common proxy for the U.S. investment-grade bond market — and the primary tracking benchmark for core bond index funds. The index is a representation of U.S. dollar-denominated, investment-grade, fixed-rate taxable bonds. It includes 9,100 issues totaling $17.6 trillion as of the end of November — comparable to the market capitalization of the Standard & Poor’s 500 index, which was $19.5 trillion. Yet the U.S. Aggregate represents only 49 percent of the U.S. bond market and a mere 17 percent of the $100 trillion global bond market.

Some investors believe the U.S. Aggregate represents the total bond market. It does not. It is simply the aggregate of the Barclays U.S. Treasury, Government-Related,* Investment Grade Corporate and Securitized** indexes. The bond market has grown considerably since the Agg’s launch. That said, the U.S. Aggregate remains more narrowly focused (see chart 2).

The U.S. Aggregate Does Not Represent the Total U.S. Bond Market

The U.S. Aggregate is a subset of the domestic bond market, much as the S&P 500 is a subset of the domestic equities market. Just as investors regularly seek to diversify their large-cap stock exposure by including a range of complementary sectors, styles and market caps, they should consider a similar approach in fixed income. A number of the sectors excluded from the U.S. Aggregate, such as Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities, nonagency mortgage-backed securities and high yield, have typically outperformed during periods of rising rates. We believe these securities can help improve the risk-reward profile of a core bond portfolio when actively managed in a carefully monitored, risk-focused manner.

Investors are attracted to indexes for a number of reasons. High on the list is consistency. Most asset allocators assume that the risk characteristics of their benchmarks maintain similar attributes over time. The U.S. Aggregate provides consistency in terms of the methodology it employs to construct the index; however, it does not necessarily provide stable risk exposure over time.

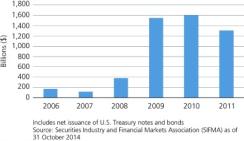

Barclays determines the weighting of the U.S. Aggregate by the amount of outstanding debt. In other words, as an issuer floats more bonds, that issuer becomes a bigger proportion of the index. Indexes that are weighted by the amount of debt that a bond issuer floats require careful monitoring whenever one or more issuers can materially affect the overall composition of the index. Since the financial crisis, the government has assumed an even greater presence in the U.S. bond market and is now the effective backer of approximately 70 percent of the debt in the U.S. Aggregate. One reason for this is the federal takeover of government-sponsored enterprises Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in 2008, which increased the amount of debt with effectively explicit government backing. This modification was followed by an unprecedented level of direct Treasury issuance (see chart 3).

Big Spender: U.S. Treasury Issuance in the Years Surrounding the Financial Crisis

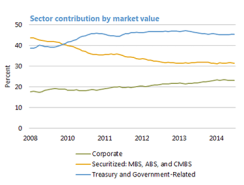

Lower interest rates have also led investment-grade companies to issue more debt. The volume of corporate issuance increased both the percentage of corporate bonds in the Agg and the duration that the sector contributes to the index (see charts 4 and 5).

The Path to Increased Duration in the U.S. Aggregate

Many companies have used bond proceeds to buy back shares following the financial crisis. The firms’ capital structures subsequently have been altered, and in a number of cases firms have more leverage. Taken together, this means that index investors have assumed greater exposure to more levered companies, highlighting the need for an active credit-review process. The average credit quality of the corporate bond component in the Agg has slipped from A2/A3 to A3/Baa1 as the proportion of Baa-rated bonds has increased (see chart 6).

Barclays Aggregate: Corporate Bond Sector, Then and Now

Armed with this information, investors should determine the best approach for gaining core bond exposure today. How does the current risk profile of the index affect the choice between indexing or active management?

The case for indexing is based on gaining market exposure at low fees. By design, index funds have no mechanism to actively manage risks inherent in the index. Lacking this active risk management, index investors are simply along for the ride, fully exposed to all of the changes to the Agg, including a 50 percent increase in duration since this time six years ago. The case for active management is most often associated with the opportunity to outperform a benchmark. An equally important advantage today, however, is the potential to improve upon the risk profile of the index. In addition, in the current low-return environment, the excess returns generated by skilled active managers contribute a larger proportion of total portfolio return.

Whereas the U.S. Aggregate may serve well as a benchmark, we believe it does not serve well as the basis for an index fund for core bond investors. Active management can be a better solution, offering investors the benefits of core bonds while retaining a focus on mitigating risk and generating higher returns.

*Government-debt includes agency, local authority, and U.S. dollar-denominated sovereign and supranational debt, from both developed and emerging markets. **Securitized debt includes agency mortgage-backed securities, commercial asset-backed securities and commercial mortgage-backed securities.

James Moore is a managing director, co-head of the investment solutions group and leader of the global liability-driven investments product management team; and Scott Spalding is an executive vice president and head of the bank trust group, both at PIMCO's headquarters in Newport Beach, California.

Get more on fixed income.