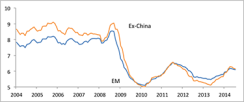

Having been in tightening mode from mid-2013 until the second quarter of this year, emerging-markets central banks have recently reversed course. The aggregate, gross-domestic-product-weighted, emerging-markets policy interest rate, which rose roughly 75 basis points during the hiking cycle, has dropped nearly 10 basis points since April. Given that China’s formal policy interest rate has not moved at all during this period, the ex-China figure has made significantly wider moves up and down (see chart 1). After several years of weak economic performance, this shift in the direction of monetary policy should reinforce, at the margin, recent signs of cyclical improvement. Still problematic inflation and looming tightening by the U.S. Federal Reserve, however, will likely limit the extent of further rate cuts, preventing central banks from forcefully supporting growth.

During the past year emerging-markets monetary policy action has occurred in a fairly concentrated fashion, meaning significant tightening efforts in a small number of key economies. As chart 2 shows, the number of hikes each month has either barely exceeded or fallen short of the number of cuts. But with Brazil, India, Indonesia, Russia, South Africa and Turkey all having raised rates, the effect on the overall emerging-markets policy stance has been large. Much of the tightening has taken place in countries whose exposure to tightening global financial conditions was revealed by 2013’s jump in U.S. bond yields. This year’s bond rally, combined with tentative improvement in external finances in several of these economies, has greatly lessened pressure on emerging-markets currencies. Meanwhile, by early 2014, given prevailing sluggishness in most emerging-markets economies, the rise in inflation provoked by earlier currency depreciation had ended. These factors in turn facilitated a shift in policy stances. Out of the countries just mentioned, only South Africa has tightened since April, and during the past three months Turkey has reversed a significant portion of the earlier tightening.

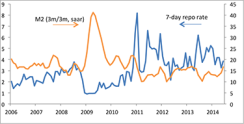

China, meanwhile, has followed a broadly similar course since mid-2013. Policy tightened in the second half of last year, partly in response to a midyear surge in growth that threatened to push up inflation and exacerbate existing imbalances in the economy. With growth subsequently slowing sharply, perhaps by more than the authorities had expected, policy turned much more supportive in early 2014. Short-term interest rates fell and, more important, growth in credit supply accelerated (see chart 3). With export growth having stayed fairly soft though mid-2014, this easing of financial conditions, along with support from fiscal loosening, appears to have played a major role in generating the reacceleration of Chinese growth that took place in the second quarter.

Scope for additional easing in emerging-markets monetary policy appears limited at this point. For one thing, the emerging-markets inflation picture has worsened at the margin. Aggregate emerging-markets consumer price index inflation moved up from 3.8 percent year-over-year in February to 4.4 percent in May, and the monthly run rate has accelerated even more strongly. Although inflation has continued to decline in a few major emerging-markets economies, like India and Poland, in others, such as Brazil, it remains at or near the top of central bank target ranges. Emerging-markets currencies, which rebounded earlier this year, have stabilized again, meaning foreign exchange appreciation will likely do little to pressure inflation downward from here (see chart 4). Meanwhile, Fed tightening is approaching. Market expectations for the first rate hike have firmed up around the middle of 2015. Given that external imbalances persist in many emerging-markets economies, higher U.S. short-term interest rates would likely produce renewed depreciation pressure on currencies, which — as was the case in 2013 — emerging-markets central banks will want to resist, given that inflation remains high. In the case of China, the most recent round of policy easing has further fueled the economy’s credit dependence and raised already high leverage ratios. The authorities seem unlikely to want to press the accelerator much more firmly now that growth has rebounded.

Without much room for policy easing, the emerging-markets cyclical outlook depends greatly on what’s happening in developed markets. Greater demand from developed economies for imports appears to be bolstering some emerging-markets economies, most notably Mexico, but emerging-markets exports as a whole continue to grow sluggishly — with emerging-markets Asia, ex-China, perhaps suffering particularly at the moment from the tax-related plunge in Japanese spending. The aggregate emerging-markets manufacturing purchasing managers index has lagged behind that of develop economies for more than a year (see chart 5). Stabilization in Japan and strengthening in the U.S., however, should generate at least some lift for emerging markets. Thanks in part to China, overall emerging-markets GDP growth appears to have stepped up to 4.1 percent in second-quarter 2014 from a first-quarter reading of 3.4 percent, the weakest figure of this current expansion. Given a more favorable developed-markets backdrop, emerging-markets growth will likely accelerate further, to roughly 5 percent on average in the second half of the year, still close to a percentage point below the estimated long-run trend rate. More robust gains await greater ability to add domestic policy support to the benefits of stronger exports.

Michael Hood is a market strategist for J.P. Morgan Asset Management. For additional Global Market Insights, please visit jpmorgan.com/institutional.

Get more on emerging markets.