Back in October, we wrote about the GDP growth gap between the U.S. and Mexico that opened during the first three quarters of 2013. At the time we argued that the unusual differential stemmed from, first, the contrasting dynamics of the two countries’ construction sectors and, second, the U.S. expansion, which appeared to be benefiting domestic producers at the expense of imports. We argued that these effects would fade over time and that the Mexican economy would strengthen as the U.S. itself accelerated.

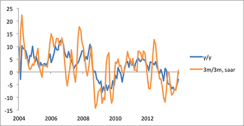

But Mexico’s lag has worsened during the past few months. The country’s gross domestic product climbed a meager 0.7 percent quarter-over-quarter, seasonally adjusted annual rate, during the fourth quarter of 2013, compared with 3.2 percent U.S. GDP growth. Although the latter figure will likely suffer downward revisions, the U.S. economy is distinctly outperforming that of Mexico. According to the latest figures, U.S. growth averaged 2.7 percent last year, versus 0.7 percent in Mexico (see chart 1). Moreover, the two economies’ manufacturing cycles, which had been tightly linked during the first several months of 2013, separated toward the end of the year, with Mexican manufacturing shrinking as its U.S. counterpart expanded at a healthy pace. These developments make the earlier explanation look incomplete, although eventual normalization of the U.S.-Mexico link still appears likely.

Mexican industrial production continues to stagnate, in contrast to U.S. industry, which accelerated strongly both at the start of 2013 and again during the fourth quarter (see chart 2). For much of last year, manufacturing in Mexico outperformed overall industry, with the difference mostly reflecting weakness in construction. But manufacturing activity also fell in the fourth quarter, just as construction was stabilizing (see charts 3 and 4). The earlier construction swoon appears related to financial difficulties at Mexico’s main homebuilding companies and to slow project execution in the early days of the new federal administration, a typical pattern. These effects are passing, although Mexico continues to lack the strong input from construction that — even after the mid-2013 rise in longer-term interest rates — has benefited the U.S. economy during the past two years.

Three factors likely account for much of the contrast between recent manufacturing strength in the U.S. and the sector’s stumble in Mexico. First, U.S. exports surged in late 2013, partly in response to firmer international growth. Mexico, with its greater focus on the U.S., did not benefit as much from that improvement. Second, U.S. manufacturers built up inventories aggressively during the second half of 2013, behavior not mirrored in Mexico — and which, in the U.S., seems to have already begun to reverse. Third, the modest acceleration in U.S. final domestic demand that took place in the second half of 2013 did not do much to boost imports. U.S. imports grew very weakly in the fourth quarter relative to overall GDP, continuing a pattern evident since the start of the present expansion (see chart 5). That shift probably owes in part to the completion of the globalization process, with emerging-markets economies no longer benefiting from this tailwind.

Given the modest growth in U.S. imports, Mexican exports are behaving as expected. If one strips out oil and agriculture to focus just on manufactures — the category of shipments influenced by the exchange rate and overall competitiveness — U.S. purchases from Mexico actually grew a little more rapidly last year than did overall imports (see chart 6). Mexico has not consistently gained market share in the U.S. since China joined the World Trade Organization, but neither has it lost shelf space. Just as with total U.S. imports, though, Mexican exports to the U.S. appear to have stagnated in seasonally adjusted terms during the fourth quarter of 2013, helping to explain softness in manufacturing.

In retrospect, Mexico’s lead over the U.S. in overall growth in 2011 and 2012 likely set up the economy for some negative payback. In those two years, Mexican quarterly GDP gains averaged 3.7 percent, versus 2 percent north of the border. Just as today’s lag looks unusual by historical standards, so too does that earlier outperformance appear large relative to longer-run trends. During that period, the U.S. economy suffered from weak international growth, especially in the euro zone, and intense domestic deleveraging. Both factors weighed disproportionately on U.S. economic expansion. The passing of these influences appears to be helping the U.S. more than Mexico.

Data for early 2014 suggest that one-off boosts to U.S. growth in late 2013 are now unwinding. The two economies seem likely to reconnect soon, especially with the Mexican construction sector seemingly past its bottom. Recently implemented tax hikes in Mexico, however, may dampen consumer spending for a time, delaying convergence. More generally, with globalization seemingly having played itself out, the benefit of “easy” international market-share gains is no longer operating in favor of emerging economies like Mexico. True, Mexico failed to pick up share within U.S. imports during the past decade or so. But overall, imports were still outgrowing the broader U.S. economy, providing support to Mexico that may no longer prove available.

Meanwhile, the vaunted U.S. manufacturing revival, which had been expected to benefit the entire North American supply chain, is proving slow to materialize. Whereas broad trends in Mexico’s economy will likely continue to depend on developments in the U.S., stronger U.S. growth will likely not exceed 1-for-1 the Mexican data. Restoring the persistent outperformance of Mexican growth relative to the U.S., evident from the mid-1990s until recently, will likely depend less on the traditional U.S. export channel and more on successful implementation of sweeping reforms, intended to raise investment and productivity, recently approved by Mexico’s legislature.

Michael Hood is a market strategist for J.P. Morgan Asset Management.

See J. P. Morgan’s disclaimer.

Read more about emerging markets.