Italy’s Banks Bolster Capital, Hope for an Economic Rebound

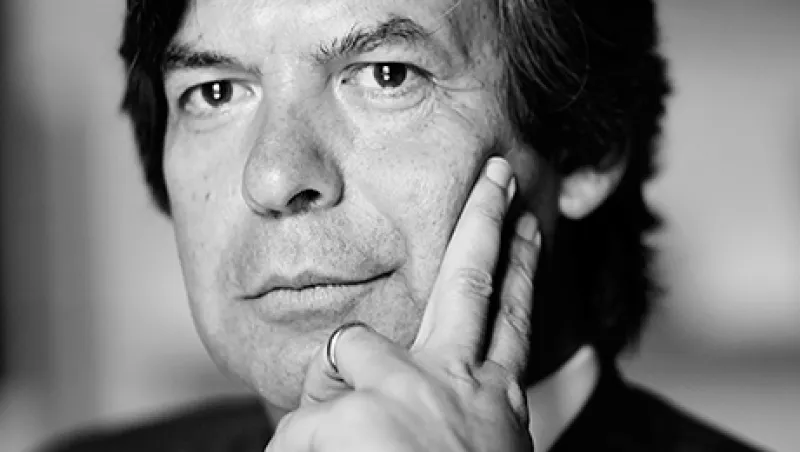

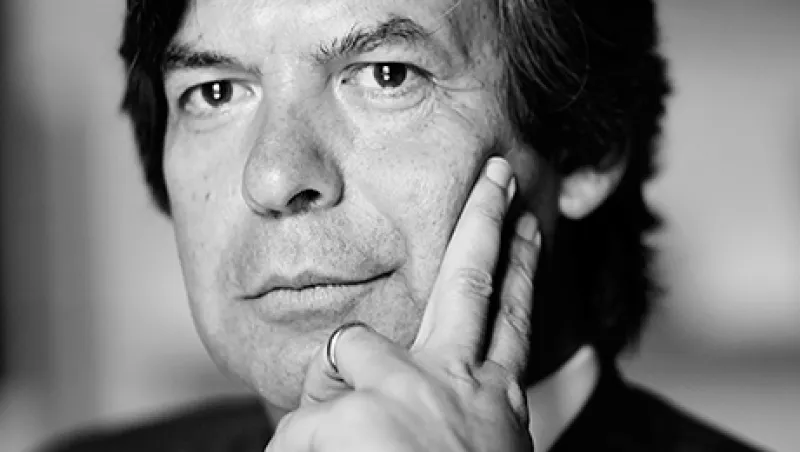

Carlo Messina's Intesa is among a number of Italian banks that are finally addressing bad loans ahead of the ECB’s review; will the economy enable them to return to health?

Charles Wallace

September 29, 2014