Early last November bankers at Credit Suisse Group in New York had planned three days of calls to field questions on the newest securitization asset class: rooftop solar power contracts. They ended up spending five days chatting with investors about the landmark bond offering by energy provider SolarCity. “The buzz surrounding this deal was at least as great as, if not greater than, it has been for other esoteric assets,” says Stephen Viscovich, a director in the securitized assets group at Credit Suisse, which was sole structuring agent and book runner for the transaction.

Companies like San Mateo, California–based SolarCity that install solar panels atop residential and commercial buildings and sell the power to those customers have eyed securitization for years as a way to lower development capital costs and expand their business. But it took until November 2013 to wrap the first bond deal backed solely by small rooftop solar installations. Among the obstacles: The young solar power industry offered little data for ratings agencies, and incorporating tax benefits into deal structures proved complex.

SolarCity issued $54.43 million worth of investment-grade notes, with a 4.8 percent yield and a December 2026 maturity date. The underlying assets consist of 5,033 photovoltaic systems in 14 states; the portfolio is 71.1 percent residential and 28.9 percent commercial or government. Ten investors each took a roughly $5 million slice, according to SolarCity CFO Robert Kelly, who says they include hedge funds, pension funds, alternative-energy funds and life insurers. “We picked a relatively small deal first time up,” Kelly explains. “We wanted to create a new capital source and open up the market.”

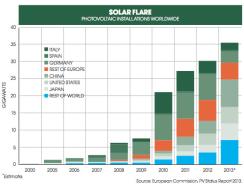

Investment in the U.S. solar industry topped $15 billion last year, compared with less than $3 billion in 2008, the Washington-based Solar Energy Industries Association estimates. The residential market continues to see the fastest growth: Through the third quarter of 2013, residential photovoltaic installations were up 49 percent year-over-year, to just under 200 megawatts. Some 31,000 U.S. homes installed solar panels in the third quarter, a new record.

To fund its expansion, SolarCity will issue about $200 million worth of notes every three months, Kelly predicts. The company aims to bring 100 megawatts of new installations online each quarter, enough to power 17,000 homes and businesses. As of the third quarter of 2013, SolarCity enjoyed a 26.2 percent market share in the U.S., with more than 72,000 installations; predicted future cash flow from its existing contracts stood at $1.7 billion, versus $500 million in 2011.

Although they declined to comment, California rivals such as Sungevity, SunPower Corp. and Sunrun may pursue similar offerings. “The next year or two will likely see around $600 million to $1 billion in issuance,” says Credit Suisse’s Viscovich. “But there is no reason why in a couple of years this market can’t be a couple of billion dollars,” he adds, putting the average issuance at about $100 million.

Jigar Shah, founder of St. Peters, Missouri–based solar company SunEdison, has long pushed for the securitization of solar assets. “It is the single most important way in which the solar industry will be able to grow,” Shah says. “If you look at the yields, they are very attractive for investment-grade-rated paper.”

Standard & Poor’s rated SolarCity’s pool of contracts BBB+. To help win that rating, the company hired what is now Høvik, Norway–based engineering firm DNV GL to do a technical and operational review. Getting S&P comfortable with SolarCity’s assets and a lack of historical data was crucial to the deal, Viscovich notes. Some investors were skittish too. Denver, Colorado–based Janus Capital Group passed on SolarCity because of the relatively long time — seven years — it will take to recoup an initial investment.

“The most critical thing for the investors is understanding the energy payments and how that is different from mortgages and car payments, which are also securitized,” Kelly says. SolarCity customers sign 20-year contracts, he notes; also, because energy payments are operational rather than purchasing costs, consumers and businesses tend to make them before mortgage and loan installments. Combined with low default rates, solar contracts provide clarity for bond investors, contends Kelly, who expects steady deal flow: “I think my competitors are going to jump in pretty quickly.” • •

Get more on alternatives.