The downside surprise in the euro zone consumer price index for October solidified broader concerns about falling inflation in developed economies. After rebounding during the first two years of the recovery, inflation in developed markets has drifted lower since mid-2011 and generally stands below central bank targets. The European Central Bank reacted quickly to the sub–1 percent figure for October and cut its policy interest rate the following week. Given considerable slack in developed economies, however, inflation may drop further. Central banks are likely to remain highly accommodative for an extended period to come.

In emerging markets the inflation picture looks quite different. With unemployment rates hovering around long-term averages, these economies appear to be operating near their full potential. Correspondingly, emerging-markets consumer price inflation has been tracking sideways since 2012 and has edged higher in recent months. In the aggregate, gross-domestic-product-weighted EM inflation ticked up to 4.2 percent year-over-year in September, compared with 4.1 percent in August and 4 percent at the end of 2012 (see chart 1). The sequential trend inflation rate (three months over three months, seasonally adjusted annual rate) has risen more sharply since midyear, reaching 5.5 percent in September. Partial figures for October do not suggest significant relief, with the year-over-year rate likely holding steady or moving down one tick, to 4.1 percent. Moreover, stable-to-rising inflation has come despite declines this year in oil and food commodity prices, which loom particularly large in emerging-markets consumer price baskets.

Inflation’s resilience in emerging markets carries with it three implications connected with the structural concerns that have beset these economies’ financial assets during the past year. The first is limited policy flexibility. During 2013 high inflation has tied the collective hands of emerging-markets monetary policymakers. With inflation running close to or above official targets — generally around 3 percent in emerging markets, though several, like Brazil at 4.5 percent, are higher — central banks are engaging in only limited easing, despite sluggish growth. Indeed, the Central Bank of Brazil’s Monetary Policy Committee (Copom) launched a rate-hiking cycle when growth was running at roughly 2 percent. Although the cyclical picture has been improving, many emerging-markets economies are struggling to adapt to the rising global interest rate environment. As capital inflows slow, emerging markets with large current-account deficits need to narrow these gaps. Given current inflation levels, central banks will likely allow currency depreciation — which risks pass-through into local prices — to accomplish only a small portion of that task of narrowing payments imbalances. Emerging-markets exchange rates already slipped by some 9 percent during the summer. Their more recent sell-off unwound most of the September rally (see chart 2). With terms of trade unlikely to make a significant impact, lower demand will need to shoulder much of the burden. Indonesia is a case in point. Its central bank has raised rates by 175 basis points since June, showing a clear focus on improving external imbalances via weaker domestic absorption.

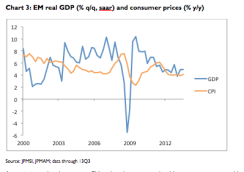

The second concern for emerging-markets economies weighed down by high inflation: potential slower growth. Inflation has remained stable in emerging markets during 2013, even as growth has fallen short of expectations, and looks particularly disappointing when compared with figures from before the 2008 financial crisis. A poorer growth-inflation trade-off suggests that economic potential in emerging markets has slowed considerably. From 2005 to 2006, for example, GDP growth in emerging markets averaged 7.7 percent, but inflation slowed during the same period (see chart 3). In 2013 growth has run at a 4.5 percent clip, with inflation flat to rising. Some of this disparity stems from different starting points. In terms of economic activity, spare capacity was fairly abundant in emerging markets during the early 2000s; inflation in these economies was near 5 percent at the end of 2004. But the stark difference in performance today also appears to reflect a slowdown in potential growth, such that even two years of emerging-markets growth of below 5 percent has not yet succeeded in creating sufficient slack to put downward pressure on inflation. This observation is a particular worry in the largest emerging markets, including China, India and Brazil. All have been growing at poor rates compared with previous norms, but in none has inflation fallen significantly during the past year. Some of the apparent slowdown in potential growth may prove temporary. In both Brazil and India, for example, policy stances perceived to be hostile to private enterprise appear to have damaged business capital spending, a situation that could be reversed fairly quickly. But the widening growth-inflation gap suggests that our 5.9 percent estimate of potential emerging-market gross domestic product growth.

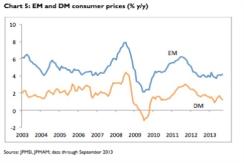

The third implication: Real exchange rates in emerging markets should trend upward during the medium term, on the back of growth rates — even diminished ones — that greatly exceed those of developed markets. This dynamic has been the case during the past ten years or so, with the aggregate emerging-markets, trade-weighted, real effective exchange rate rising about 35 percent, or 3.1 percent a year, from the end of 2003 until October 2013 (see chart 4). This pattern should continue even if emerging-markets growth is structurally slowing, given that its expansion rate nonetheless will comfortably top the developing-market pace. Real currency appreciation, however, takes place through two mechanisms: spot movements in foreign exchange and changes in local prices, meaning faster inflation than in a given country’s trade partners. The inflation gap between developed and emerging markets has widened, and if recent trends hold, it could be even more broad. In September the difference reached 3 percentage points (4.2 percent versus 1.2 percent), compared with 2 to 2.5 percentage points before the 2008 crisis (see chart 5). Emerging-markets real foreign exchange rates appreciated fairly strongly during the first half of 2013. The subsequent correction only returned the aggregate to end-2012 levels. Sideways-to-down moves in emerging-markets nominal foreign exchange, then, are likely generating less future value than would have been the case in the mid-2000s.

Michael Hood is a market strategist for J.P. Morgan Asset Management.

Get more on emerging markets: “Why a Slowdown in Emerging Markets Could Be a Good Thing”