How should one rate the rating agencies? Some seem to think that you can evaluate ratings by looking at their impact on market prices. If a rating change is not accompanied by a change in bond spreads — or if bond prices diverge markedly from levels implied by ratings — some see it as a “failure” by the ratings providers.

That is the wrong test. Ratings and market indicators (bond spreads and credit default swap prices) cannot be directly compared because they are fundamentally different. They are generated by very different processes and are often driven by different factors. Ratings provide a long-term subjective view of creditworthiness based on fundamental credit analysis, whereas market-based indicators reflect the ebb and flow of market sentiment, the liquidity of a security and many other short-term technical factors.

If the market reacts differently — or indifferently — to a rating action, that does not say anything about the quality of the rating action. Take euro zone sovereign ratings, for instance. For many years before the recent debt crisis, the market valued debt issued by countries such as Greece and Italy roughly on a par with AAA-rated German government bonds, although their credit ratings were significantly lower — and even after they were further downgraded from 2004–’05. It is a good example of how markets are volatile and prone to over- or undershooting, whereas ratings remain relatively stable.

Credit ratings are forward-looking opinions about the relative creditworthiness of borrowers and the securities they issue. The higher the rating of an issuer or debt issue is, the lower the probability of default, in the rating agency’s opinion. To judge the performance of ratings, therefore, you have to look at their correlation over time with defaults, not with short-run movements in market prices.

Analyzing the Default Studies

Standard & Poor’s studies show that corporate and government ratings have continued to perform well as indicators of default risk since the financial crisis. They consistently demonstrate a close match between ratings and defaults across all regions and all periods. The higher the rating is, the lower the incidence of default, and vice versa. And higher ratings have proven progressively more stable than lower ratings.

Globally, none of the 66 rated companies and financial institutions that defaulted in 2012 had S&P investment-grade ratings (BBB- and above) at the start of the year, and about 80 percent of them were rated B- or lower at the beginning of 2012. Fully 90 percent of corporates globally that defaulted last year — including all 9 European defaulters — had initial ratings that were sub-investment-grade (BB+ and below). Of the 10 percent that were originally rated investment grade, the average time to default — the time between the first rating and the date of default — was 17.6 years.

Since 1981, only 1.1 percent of companies globally that were rated investment grade have defaulted within 5 years, compared with 16.4 percent of companies that were rated sub-investment-grade. Ratings continue to remain relatively stable. Some 72 percent of corporate ratings globally were unchanged in 2012, similar to the annual average of the past ten years.

Sovereign ratings, likewise, have an excellent long-term track record. Since 1975, an average of 1 percent of investment-grade sovereigns rated by S&P have defaulted on their foreign currency debt within 15 years, compared with about 30 percent of those in the non-investment-grade category.

Sovereign ratings have been no more volatile than ratings on companies and financial institutions. In 2012, we downgraded 17 percent of rated sovereigns and upgraded 8 percent, while 75 percent were unchanged. Sovereign ratings have also exhibited greater stability at higher rating levels than at lower levels.

As we have said many times, we were very disappointed by the performance of our ratings on certain U.S. mortgage-backed securities. We regret that, like many others, we did not foresee the speed and severity of the U.S. housing downturn. In other areas of structured finance, including mortgage markets outside the U.S., our ratings have generally held up well in the crisis and have continued to perform strongly.

Outlook for European Corporate Defaults

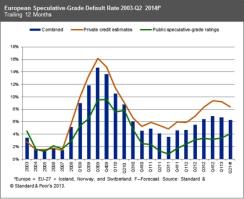

As things stand, the default rate for sub-investment-grade, or speculative-grade, companies in Europe remains elevated. There were eight corporate defaults in the first quarter of 2013 in the 27 European Union countries plus Iceland, Norway and Switzerland, resulting in a trailing 12-month speculative-grade corporate default rate (combining our public rating and private credit estimate portfolios) of 6.7 percent. This rate is slightly down from the 6.9 percent at year-end 2012 (see chart).

Because these defaulters were mainly midsize companies, the exposed debt amounted to only €5.2 billion ($6.9 billion), far below the €15.2 billion of affected debt in the first quarter of 2012. As a result, the default rate by value has fallen to only 3.0 percent from a revised 4.3 percent at the end of 2012, substantially below the 5.0 percent average over the last cycle that started in 2008.

Looking ahead, we anticipate that the corporate default rate will be 6.3 percent at the end of June 2014. This is slightly higher than our previous 6.1 percent projection for March 2014, although lower than what we have experienced in recent quarters.

Almost five years after the collapse of Lehman Brothers Holdings, it is clear that the economy of the euro zone remains reliant on support from the European Central Bank and sustained recovery remains elusive. This is particularly problematic for the weaker peripheral countries, such as Spain and Italy, which are experiencing a severe recession exacerbated by a contraction in credit availability from local banks. But even other countries, such as France, are not immune.

Indeed, the most notable development is the material increase in defaults for French companies, all of which were sponsored leveraged buyouts, with missed principle payments being a factor in six cases. Although weak operating performance resulting in balance-sheet restructuring was a common factor underlying most of these defaults, overambitious expansion, bad management and an unwieldy syndicate group were the proximate cause for several of the defaults. This takes the trailing 12-month default rate in France to 10.5 percent from 8.7 percent at the end of 2012, considerably above the current average European default rate of 6.7 percent.

We remain concerned about the broader effect of the financial crisis on the credit quality of companies with significant business exposure to the euro zone periphery. Larger companies, in the main, have been able to protect their financial risk profiles by refinancing maturing debt through the bond market. Smaller companies with weaker financial risk profiles, however, remain highly reliant on their relationship banks to roll over existing debt. Loan-funded LBOs originated in 2006–2008 have also benefited from collateralized loan obligations investors’ acquiescing to amend-to-extend transactions that delay the maturity of their leveraged loans.

In this context, recent actions undertaken by the Bank of Spain lift the veil on the widespread use of forbearance to roll over loans to companies that may have longer-term credit issues. Specifically, the central bank notes that Spanish banks appear to have been inconsistent in the application of accounting policies for loans that have been refinanced or extended. As a consequence, the Bank of Spain is concerned that banks may underestimate default risk and delay their recognition of impairment, undermining efforts to restore confidence in the quality of Spanish banks’ balance sheets. Spanish banks’ underestimation of corporate default risk also raises broader questions about the extent to which dubious forbearance practices have been applied in other jurisdictions.

The U.S. Outlook

S&P Global Fixed Income Research expects the U.S. corporate trailing 12-month speculative-grade default rate will increase to 3.3 percent by March 2014 from 2.5 percent as of March 2013. Although a rise, that is still below the long-term average of 4.5 percent.

This forecast is partly based on assumptions that the U.S. economy will grow by 2.7 percent in 2013 and unemployment will decline to less than 7 percent by first-quarter 2014. We do not expect the Federal Reserve to raise the federal funds target rate until 2015, even though it is likely to taper off asset purchases by the end of this year or early 2014. We expect that the housing market will continue to improve and the manufacturing sector will benefit from the relatively cheap natural gas prices.

Investor demand for higher-yielding securities helped push new corporate speculative-grade-bond issuance in the U.S. to a record high of $98 billion during the first four months of 2013. Despite persistent investor concerns regarding Europe’s fiscal challenges and the continued uncertainty in parts of the Middle East, easy access to the credit markets has helped keep default occurrences low in recent months.

Investors appear to have become more selective in recent months, however. New bond issuance rated B- and lower comprised only 21 percent ($21 billion) of the total speculative-grade bonds that came to market in the first four months of 2013, compared with nearly 37 percent ($42 billion) during the last four months of 2012, according to S&P Global Fixed Income Research. A sustained disinterest in lending to companies at the lower end of the rating spectrum could trigger an increase in defaults, since these companies tend to have less financial flexibility and are often reliant on the credit markets for capital to fund operations or refinance maturing debt.

The Real Test

There is no mystery about ratings performance. It can be found in the data published by ratings agencies and others, which S&P, for instance, makes freely available to market participants and the wider public. It also appears in the “ratings comparison” website maintained by the European Securities & Markets Authority, showing the comparative performance of 18 registered or certified ratings agencies in the European Union.

Ratings are subjective opinions about the future, which can be affected by unpredictable events and factors; they are not guarantees about default risk. Investors can sometimes disagree, as reflected in market prices. Yet the evidence shows that ratings in general continue to be closely correlated with defaults. That is the real test for rating the raters.

Yann Le Pallec is executive managing director for Europe, Middle East and Africa at Standard & Poor’s Ratings Services.

Read more about .