Victor Westerlind knows how it feels to get burned by the sun. Starting in 2006 his venture capital firm, RockPort Capital Partners, threw more than $63 million at ill-fated solar cell producer Solyndra. The Fremont, California–based company declared bankruptcy in 2011 and went on to lose its private investors nearly $1 billion, as well as most of its $535 million loan from the U.S. Department of Energy.

“Solyndra didn’t make us run away from solar,” says Westerlind, a general partner of RockPort, an $850 million firm with offices in Boston and Menlo Park, California. “But it made us more prudent about companies’ business plans and more focused on keeping investments to tens of millions and not hundreds of millions.”

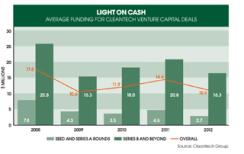

Westerlind isn’t alone. Mindful of the risks in clean technology, early-stage investors are thinking twice about solar power, biodiesel plants and other capital-intensive plays. Last year global venture capital investment in cleantech fell 33 percent, to $6.46 billion, San Francisco–based research and advisory firm Cleantech Group reports.

In search of companies that can earn a profit with minimal up-front investment, venture capital shops are turning to an emerging category called cleanweb. Companies in this sector typically leverage technologies such as smartphones, the Internet and social media to encourage better use of energy, water and other limited natural resources.

“The cleanweb space has got capital efficiency and high scaling potential, and it’s differentiated and disruptive,” says Sunil Paul, the venture capitalist credited with coining the term “cleanweb” in 2011. Early that year the firm he co-founded, San Francisco–based Spring Ventures, devoted itself to cleanweb. Since 2011, Paul has been CEO of SideCar, a San Francisco company whose mobile app connects drivers with people seeking rides.

Investors like cleanweb’s low technology risk as well as its light capital requirements. The mobile and Internet technologies it relies upon to innovate are already in wide use, Paul notes. But cleanweb also owes its growing popularity to a proliferation of devices in homes, office buildings and elsewhere that gather detailed information about energy consumption. The resulting flood of data has prompted companies to create software that makes the power grid more efficient and helps consumers save energy.

One device driving such start-ups is the smart meter, which constantly measures energy use and sends that data back to a utility. By the end of 2012, 285 million smart meters had been installed worldwide, up from 60 million three years earlier, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance, a unit of the news and information giant. BNEF estimates that the total will reach 900 million by 2018. Although the scale of investment in cleanweb is still unknown, the so-called smart-grid space offers a glimpse. Globally, investors poured $13.9 billion into smart-grid technologies last year, according to BNEF, which predicts that number will climb 81 percent, to $25.2 billion, by 2018.

Opower, an Arlington, Virginia–based start-up, shows how hardware like smart meters can spawn business opportunities. Utilities hire Opower to provide reports on customers’ energy use; in turn, it recommends ways to improve energy efficiency. Its investors include venture capital firms Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers and NEA, both based in Menlo Park.

Some observers complain that investors are paying too much attention to cleanweb. “I’m hearing this question a lot: ‘But what does the world need?’ ” says Sheeraz Haji, CEO of Cleantech Group. “Big companies and environmentalists are saying, ‘We need breakthroughs at the fundamental research level; we need better materials; we need to drive the costs of solar panels down; we need to dramatically improve energy storage. Who is going to fund energy storage if everyone is chasing cleanweb deals?’ ”