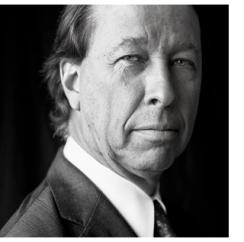

Ara Hovnanian, CEO of Hovnanian Enterprises, knew little about GSO Capital Partners before the credit-oriented alternative asset manager offered the struggling homebuilder a lifeline last year. Douglas Ostrover, the “O” in GSO, invited him to lunch at Manhattan’s Core Club in July 2012, just as the U.S. housing market was showing a few signs of life. The then-54-year-old CEO figured he had little to lose by listening to Ostrover’s pitch. His company had been bleeding money for six years and had used up every penny of its capacity to issue secured debt. With no bank willing to lend to it, the Red Bank, New Jersey–based homebuilder had become a target for short-sellers; investors were betting billions of dollars in credit default swaps that the company Hovnanian’s father and three uncles had founded in 1959 would go belly-up. Hovnanian, who had lived through several real estate cycles, was shocked when Ostrover told him the price of the five-year CDS contracts on Hovnanian implied a 93 percent probability of default. “The market is saying you’re going bankrupt,” Ostrover added.

GSO, which is owned by private equity giant Blackstone Group, had spent six months digging into the finances of Hovnanian and had been buying up its equity, secured debt and unsecured debt since March. Ostrover, now 50, who helped build the leveraged-finance business at investment bank Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette during the 1990s, explained his idea for solving Hovnanian’s liquidity problems. The company would sell its property inventory to a land bank created by GSO in return for a $125 million cash infusion. Over time GSO would sell the land back to the homebuilder. Ostrover asserted that not only would the market react positively to the initial financing but that the GSO-Blackstone brand would signal that there could be more behind it. “Look, the market hates your company,” he told Hovnanian. “We love your company.”

(Ostrover had his own hard-luck family bankruptcy story: His grandfather had to shutter Ostrover’s Smoked Fish on New York’s Lower East Side in the 1950s following a blackout; he couldn’t pay his creditors because his customers’ fish had rotted.)

Hovnanian, for his part, was not convinced that the market would react as positively as Ostrover suggested. “If you’ve been out in the battlefield for seven years, being shot at constantly, you don’t know what to do if the bullets stop flying,” he told Ostrover, who left the lunch uncertain whether the CEO would agree to his plan.

It took a week before Hovnanian softened, but GSO got its deal. Indeed, when Hovnanian announced the land banking deal on July 13, 2012, its stock rose, its senior secured debt traded up from 84 to 97 cents on the dollar, and the price of the CDS contracts collapsed. Traders betting against the company lost money. The stock rose 170 percent between July 2012 and the end of the year. J.P. Morgan and other Wall Street research firms changed their rating from a sell to a hold — GSO had been hoping for a buy — and Credit Suisse refinanced Hovnanian’s high-cost debt that was coming due in 2016 and that the naysayers were sure would sink the company.

“They did their homework, and they were convinced that the market was underestimating our ability to succeed in a space — housing — that they thought was recovering,” says Hovnanian. Eleven months later the U.S. housing rebound is official and Hovnanian Enterprises is flourishing, expecting 2013 to be its first profitable year since 2006. Hovnanian was the largest position in GSO’s flagship hedge fund in 2012, and the firm made 50 percent on its capital in six months.

GSO has provided much-needed credit to scores of troubled companies like Hovnanian that couldn’t tap public markets or get bank loans. The firm has financed well-known names like Chesapeake Energy Corp., struggling with weak natural-gas prices and controversy around its ex-CEO and needing capital to develop lucrative energy projects, and Sony Corp. while also providing $650 million of capital to smaller homebuilding companies like the U.K.’s Miller Group and $888 million to companies in Europe last year, including Canberra Industries, Welcome Break and EMI Music Publishing. As one of the largest creditors of MBIA and holders of its equity, GSO had a big win last month when the Armonk, New York–based provider of municipal bond insurance finally settled a dispute with Bank of America Corp. after years of wrangling over troubled mortgage-backed securities.

“In the old days a bank might have been more willing to commit its balance sheet for long-standing clients,” says Bennett Goodman, the 56-year-old “G” in GSO, who started his career at Drexel Burnham Lambert in the 1980s. “Because of the regulatory environment, it’s harder for them to do that economically. As a consequence, banks want to syndicate risk into the market — put together a road show and talk to 200 investors. But they don’t want to commit their capital. We, on the other hand, want to own the risk.”

GSO founders Goodman, Ostrover and Tripp Smith have emerged as lenders of last resort, filling the gaping financing void left by banks and opportunistic hedge funds in the wake of the 2008–’09 financial crisis. The firm follows in the footsteps of Drexel and Michael Milken, who in the 1980s invented the junk bond market for non-investment-grade companies. In the 1990s, GSO’s three founders, then working for Hamilton (Tony) James at DLJ, took up where Drexel left off, building that firm into the No. 1 leveraged-finance player, lending to blemished companies that were in some of the fastest-growing sectors of the U.S. economy, including energy exploration and homebuilding. If Drexel came up with the junk bond and DLJ created the institutional leveraged-finance market, GSO is again reinventing the concept of providing capital to non-investment-grade companies — this time as an asset manager.

“In the era of Dodd-Frank and the Volcker rule, GSO and others like it, with their ability to make commitments, have more market power than ever,” says Brian O’Neil, chief investment officer of the $9 billion-in-assets Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the U.S.’s largest philanthropic organization focused on public health and one of GSO’s first investors.

Banks may no longer have the balance sheets, but big institutional investors like sovereign wealth funds, endowments and pension funds do. To be sure, Blackstone is not the only manager to have smelled opportunity in the financing void. Depending on the product, GSO has a host of competitors, including Apollo Group Management; Ares Capital Corp. (an Apollo spin-out); Avenue Capital Group; Carlyle Group; Goldman, Sachs & Co.; J.P. Morgan Asset Management’s Highbridge Capital Management; KKR & Co.; Oaktree Capital Management; and TPG Capital.

James Coulter, co-founder of private equity firm TPG, says the opportunity is much more attractive for managers and investors now that banks — which threw cheap money from depositors at troubled companies’ financing problems and pocketed the profit — are not in the mix. “There is a place for capital formation at market rates of return and driven by problem solvers,” explains Coulter. “It’s alternative credit growing up. It’s not the Wild West, not the personality-driven days of 20 years ago. And this is good for the economy.” TPG launched its own midmarket lender after the financial crisis and has both competed and partnered with GSO.

Goodman, Smith and Ostrover founded GSO in 2005 to provide capital to non-investment-grade cyclical companies that were going through a tough patch but had tangible assets to put up as collateral to protect the firm’s downside when it lent them money. GSO was an early investor in the shale gas industry, which has been whipsawed by volatile pricing and other events. “They have a zealous approach to protecting capital, and they’ve found a way to extend credit to organizations that need it and structure it in a way that takes advantage of the environment at the time,” says Blackstone chairman, CEO and co-founder Stephen Schwarzman.

In 2008, Blackstone, looking to diversify, paid $1 billion to acquire GSO, which then had a $3.2 billion credit hedge fund, $500 million in mezzanine investments and a $4.8 billion collateralized loan obligation business. The deal wouldn’t have happened without Goodman, Smith and Ostrover’s former boss, Tony James, who had joined Blackstone as president in 2002 after Credit Suisse bought DLJ and who manages the firm’s day-to-day operations. “This was more like a family reunion than an acquisition,” says Schwarzman.

“Credit to Steve, he really trusted me on this one,” adds James, who says Blackstone was looking for an area of asset management with room to grow that would complement its existing private equity, real estate and fund-of-hedge-funds businesses. “What was a wide-open white space for us? Credit jumped off the page.”

GSO’s returns have been top quartile. According to external marketing documents, its hedge fund has delivered a net annualized return of 13.6 percent since January 2010, compared with the HFRI Fund Weighted Composite’s return of 4.6 percent for the same period. (Though the hedge fund was launched in 2005, GSO has since stripped out mezzanine and other investments into separate funds.) The firm’s mezzanine fund has one of the best records in the industry, up an average of 19.9 percent a year net since inception in July 2007. Rescue lending has returned an annualized 15.2 percent since inception in September 2009. “The GSO team has been through the ups and downs of numerous credit cycles, and they’re always worried and trying to protect the downside,” says Timothy Walsh, chief investment officer of the $74 billion New Jersey Pension Fund, which has committed to $1.1 billion in investments in five GSO funds.

Blackstone’s acquisition of GSO has been an undisputed winner. GSO represents 26.6 percent of the firm’s $218 billion in assets, on par with its $59 billion real estate business and larger than both its private equity ($52 billion) and Blackstone Alternative Asset Management hedge fund ($48 billion) businesses. GSO represented 38.9 percent of Blackstone’s $629 million of realized performance fees earned in 2012 and 16 percent of the firm’s $2 billion in economic net income last year. In 2007, the peak for the firm’s performance fees, private equity contributed the bulk of the total. Between 2005 and 2012, GSO’s assets grew at a compounded annual rate of 29 percent. That makes GSO Blackstone’s fastest-growing business in terms of both earnings and assets. Executives at two publicly traded alternatives firms say they aren’t so much concerned about Blackstone as a competitor in private equity but that they’ve been blindsided by GSO’s growth. Though hurt by the financial crisis, Blackstone and GSO have emerged as dominant players in its aftermath. Since 2008, Blackstone has more than doubled its assets.

At the same time that GSO is capitalizing on the void left by banks, it is also benefiting from historically low interest rates and unrelenting investor demand for credit investments. While non-investment-grade companies need capital, investors need yield, and alternative credit strategies like those offered by GSO provide a much-needed boost to returns for bond portfolios. “Now the emergence of alternative credit mirrors tools that equity investors have had with private equity,” says TPG’s Coulter.

The future looks bright for credit investing. Remnants of the financial crisis continue to cast a shadow on markets, especially in Europe. When Smith was pitching deals at Credit Suisse, he was constantly being undercut by in-country banks. “You couldn’t hope to compete because the banks were so aggressive,” he says. As a result, the high-yield and leveraged-loan markets never developed in Europe to the extent they did in the U.S. But that’s starting to change as European banks need to deleverage and raise capital and companies desperately require funding. GSO is hoping to be a big part of the transformation.

IN THE 1980S, WALL STREET had a clear pecking order. On top were three white-shoe firms: First Boston Corp., Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley. That’s where you wanted to land a job if you were a Harvard Business School student. The day in early 1983 that the three firms sent recruiters to the campus, Bennett Goodman was playing basketball; when the game went into overtime, he arrived too late to get into the crowded blue-chip presentations.

The only opening that day was for Drexel, which was at the bottom of the Wall Street pecking order even as it dominated the business of financing non-investment-grade companies. Goodman had never heard of the firm, but he distinctly remembers Frederick Joseph, Drexel’s CEO, passionately recounting how it financed entrepreneurs, married capital to ideas and was profoundly transforming whole industries. “I fell for it hook, line and sinker,” says Goodman. “I love the underdog.” While his friends at Harvard — including one he describes as having had pinstripes on his diapers — did summer internships at Wall Street’s toniest firms, Goodman took a job with Drexel.

There Milken was leading what’s now called the democratization of capital-raising, providing funding to small and medium-size companies that were starved for financing and whetting the appetites of investors for distressed and troubled companies that showed promise despite short-term woes. In the process, Drexel helped spark an unprecedented era of prosperity in the U.S. as companies like Ted Turner’s Turner Broadcasting System, Craig McCaw’s McCaw Cellular Communications and William McGowan’s MCI Communications Corp. rapidly expanded by using this newly available source of capital. Junk bonds also fueled the leveraged buyouts of the 1980s, when firms like KKR targeted companies that had once turned deaf ears to shareholder demands.

After earning his MBA in 1984, the Miami-born Goodman took a full-time job with Drexel in New York. He spent five years there, toiling on ten to 12 deals a year — all of them different — in a culture that rewarded Street smarts and a maniacal work ethic. Drexel was a place where analysts spent days buried in the dense financials of dicey companies. The firm honed the skills needed to look at an ugly financial situation and determine the commercial viability of a financing for both the companies and investors. In contrast to the few traditional deals a year that a junior banker at Goldman might work on, Goodman cut his teeth on such unusual transactions as KKR’s investment in Union Texas Petroleum Holdings in 1985 and Maxam’s 1986 takeover of Pacific Lumber Co. For the latter he and Joshua Friedman, then head of the capital markets group at Drexel, came up with a term sheet for a zero-coupon increasing-rate note whose complexity and model they still laugh about.

In 1987 the Los Angeles–based Milken called Goodman, who by this time focused on LBOs, telling him he should move to Beverly Hills and work for Friedman (who would go on to co-found hedge fund firm Canyon Capital Advisors). But after his wife, Meg, refused to leave New York, Goodman quickly set his sights on DLJ, a midsize investment bank known for equity research and a certain scrappiness and entrepreneurial culture. Garrett Moran, who ran the high-yield bond group at DLJ, says Goodman stalked him for six months, wanting to pitch his idea for a capital markets desk.

Goodman liberally quotes from his uncle, Skip Bertman, a former head coach at Louisiana State University who has the best baseball record in the National Collegiate Athletic Association and who took an influential role in Goodman’s life after his father passed away when he was five years old. Bertman, who built an underdog team into a profitable legend for LSU, told Goodman that success took three “H”s: hard work (in an interview his uncle calls that hustle), honesty and humility.

Hard work got him noticed at Drexel, as well as a meeting with Moran. But Goodman shunted humility aside — at least temporarily — during his lunch with Moran. The 30-year-old newly minted Drexel vice president told the DLJ executive, “I’m going to help build this big business at DLJ, and you’re going to get rich and famous.” Moran, who says he instantly liked Goodman and the wealth of experience he had gotten working on deals inside the Drexel pressure cooker, hired him. “He might have been young, but it was like a pro coming into an amateur team,” adds James, who then ran DLJ’s investment bank.

In early 1988, Goodman started building the capital markets business at DLJ under Moran and James. At that time, Drexel had a lock on the business. Take the “highly confident letter,” a piece of paper Drexel would issue to the board of a company as a promise that it would provide financing on deals. When DLJ tried issuing its own highly confident letters, they meant nothing, as DLJ had a small balance sheet. So the firm created the bridge loan, not promising capital but intended to tide the company over until it could obtain permanent financing. “On the strength of that bridge loan business, we built ourselves up into the leading firm,” says James.

In September 1988 the Securities and Exchange Commission sued Drexel for insider trading and stock manipulation. The following March, Milken was indicted for racketeering and securities fraud. In February 1990, Drexel filed for bankruptcy; two months later Milken pled guilty to lesser charges, agreeing to pay a $600 million fine and serve ten years in jail. (The sentence was later reduced to two years.)

With Drexel and Milken gone amid a recession, many market watchers thought high-yield financing would die. But although most Wall Street firms pulled out of the high-yield business, DLJ stayed in, doing some secondary trading and working with companies that felt they had been abandoned. When the markets rebounded in 1991, DLJ took over as a leading player.

In 1992, Goodman hired Ostrover from Grantchester Securities, the high-yield arm of boutique investment bank Wasserstein Perella & Co., to run DLJ’s sales and trading. Ostrover, who has a BA in economics from the University of Pennsylvania and an MBA from New York University’s Leonard N. Stern School of Business, was ranked the No. 1 salesperson by a third-party consulting firm, and Goodman and Moran decided to steal him away the day the news came out.

While Goodman loves to talk, Ostrover has to be pressed for details. He reveres his middle-class upbringing — first in Queens, New York, and later in Stamford, Connecticut — and says that when he was growing up he didn’t know anyone who worked on Wall Street. Apologizing for the seeming hokeyness of it, he refers to a black-and-white picture in his office of New York’s Orchard Street early in the past century, with unpaved, muddy roads; pushcarts; and a glimpse of Ostrover’s Smoked Fish.

In 1993, Goodman hired Smith from Salomon Smith Barney, where he worked on restructurings. Smith had joined Salomon from Drexel, leaving with a group during the bankruptcy. Two years out of the University of Notre Dame, he witnessed firsthand the toll Drexel’s failure took on senior managers whose wealth had been tied up in its stock. Smith is the third generation in his Indianapolis Irish family to graduate from the Catholic university; two of his four kids are currently studying there.

Goodman and Ostrover joke that Smith was responsible for DLJ’s success. The year he joined, the firm became the No. 1 underwriter for high-yield bonds, a distinction it would keep for 12 years. Drexel had unwittingly passed the high-yield baton to DLJ. Though the three founders couldn’t be more different, they’ve maintained their partnership without a blip for 20 years. Goodman is the storyteller of the group, Ostrover is Mr. Markets, and Smith wants to stay out of the limelight and just do deals. Though the three are equal partners at GSO, Smith and Ostrover often defer to Goodman for the final word.

In 1995, Moran moved up to chief operating officer of fixed income, and Goodman took over all of leveraged finance. DLJ used its market position to keep reinvesting in the firm, building a leveraged-loan capability and creating a derivatives business and large distressed unit. The group invented concepts such as payment-in-kind toggle bonds, with which an issuer can defer interest payments in return for a larger coupon in the future, and IPO carve-outs, whereby the parent company sells stock of a subsidiary to the public. In the late 1990s, Schwarzman, a client of DLJ’s, asked Goodman to start a credit business at Blackstone. It was the first of many overtures Blackstone’s executives would make to him.

It was DLJ’s limited balance sheet that taught Goodman, Ostrover and Smith how careful they had to be with their credit analysis and due diligence. There was little room for error. “You had to figure things out and use your smarts instead of brute strength,” Smith, 47, says. By 1999, however, DLJ was hamstrung by its small balance sheet and a business that was primarily domestic. Competition from increasingly bigger banks was fierce. The world had changed, and the firm needed a partner.

Credit Suisse bought DLJ for $11.5 billion in 2000 and combined the firm with its New York–based investment banking unit, Credit Suisse First Boston. The big Swiss bank wanted Goodman’s leveraged-finance business as well as DLJ’s merchant banking and real estate groups. Though DLJ investment banking staffers left in droves after the deal — including James, though he stayed two years as part of the merger agreement — Goodman, Smith and Ostrover flourished. Even before James left CSFB, he and Goodman talked about going off on their own. After James joined Blackstone, Goodman took over CSFB’s alternative capital division. Shortly thereafter Ostrover assumed responsibility for leveraged finance and Smith joined Goodman in the alternatives group. What the three founders have built at GSO, they originally planned for CSFB.

But in June 2004, John Mack, then CEO of CSFB in the U.S., announced he was leaving; the Credit Suisse board had decided not to renew his contract. It was a good time for Goodman, Smith and Ostrover to start their own firm. By that July the three partners had launched GSO with 25 employees and one hedge fund. The firm had purchased a small CLO group, run by Daniel Smith, from Royal Bank of Canada. Smith, who had been co-head of high-yield group among other positions at Van Kampen Investments, now runs GSO’s customized credit strategies, including CLOs, closed-end funds and Franklin Square Capital Partners, its small-cap direct lending group.

On day one Credit Suisse gave the firm more than $500 million to manage — a big part of the approximately $3 billion it had raised from outside investors, including the Bass brothers, Blackstone, Cornell University, K2 Advisors, MetLife, Notre Dame and Quellos Group (now owned by BlackRock). GSO’s hedge fund invested in public securities, mezzanine debt and distressed debt and provided some rescue lending for companies going through liquidity problems.

Fully 80 percent of GSO’s senior management team is from DLJ. Jason New, a onetime bankruptcy lawyer who had been with DLJ since 1999 and worked on some of the most complex distressed deals, such as financing Level 3 Communications and Qwest Communications, joined GSO at the start. He now manages its hedge fund. A month after its launch, GSO hired Donald (Dwight) Scott, who ran the energy practice at DLJ before joining El Paso Corp. in 2000. Houston-based Scott oversees GSO’s energy group.

In 2007, Merrill Lynch & Co. took a minority stake in GSO and the firm had its first closing for a new mezzanine fund. But its deals remained small, providing funding for companies like Pacific Lumber and Caffè Nero, a U.K. coffeehouse chain. Though it was satisfying to be on their own, Goodman, Ostrover and Smith were used to being No. 1 and having a big firm behind them. But things were changing, and they would get their chance soon.

WHEN ASKED ABOUT HIS DECISION to switch from the sell side to the buy side, Goodman says his only regret is that he didn’t make the move ten years earlier. Though he loved working on Wall Street, particularly at DLJ, Goodman wanted to spend all his time investing. “At a bank you’re working for anonymous shareholders, trying to make as much money as you can,” he explains. “It’s amorphous, and you don’t know the people. It’s a different kind of satisfaction walking into the CIO’s office for the Bass brothers.”

A deal between Blackstone and GSO, however, wasn’t a no-brainer. Private equity investors are by nature optimistic and swaggering, thinking every deal is a potential blockbuster. Blackstone’s offices on Park Avenue are nothing short of glitzy, with unobstructed views of the New York skyline and floors connected by grand staircases with polished metal banisters. No one has represented Blackstone’s opulence more than its billionaire co-founder Schwarzman, who in 2000 reportedly paid $37 million for a 34-room triplex on Park Avenue and has owned vacation properties in the Hamptons; Jamaica; Palm Beach, Florida; and Saint-Tropez.

Credit investors, on the other hand, are pessimists, aware that the upside of their investments is limited, evaluating everything that can go wrong in an effort to protect their principal. Credit geeks Goodman, Ostrover and Smith nonetheless went to Blackstone’s extravagant road show at New York’s Pierre hotel in the spring of 2007, the first time that granular detail about the private equity firm was available to the public. The trio had remained close to James after he left DLJ for Blackstone, and they knew he was interested in striking some type of deal. During the road show, Blackstone disclosed its numbers, showing heft in private equity, real estate and funds of hedge funds, but credit was an afterthought, amounting to only about $5 billion in assets. At the same time, Blackstone had relationships with almost every major institutional investor in the world, a group that had, on average, $200 million in assets invested with the firm. GSO’s investors, by contrast, had a paltry $22 million invested with Goodman, Ostrover and Smith. GSO was also overly dependent on Merrill Lynch and Credit Suisse, both of which were starting to feel pressure in the early days of the subprime crisis.

Any deal would hinge on James, who was revered by GSO’s three founders. That summer James approached Goodman — the fourth time Blackstone had tried to entice him into a deal — and stated the obvious: “In credit we’re not where we want to be. We want to buy you.”

After six months of negotiations, Goodman and his partners said yes. Although they enjoyed being their own bosses, they missed the prestige, and the deals, that came with being part of a big organization. With Blackstone they would get scale, a brand, idea-sharing with the firm’s deal makers and access to new and larger clients. Smith, who calls himself Mr. Process, was the least enthusiastic about the tie-up, concerned that they were trading away their autonomy. But the $1 billion price tag — the proceeds of which the partners rolled over into GSO funds — and the potential to take advantage of what they thought would be a huge shift on Wall Street helped alleviate their concerns.

“Blackstone allowed us to take our business from being three years old to ten overnight,” Ostrover says.

GSO and Blackstone announced the deal in January 2008. In addition to strengthening their firm’s credit business, Schwarzman and James saw benefits for its private equity operation. “Having a better understanding of credit markets, having a better idea of how we could finance a creative idea, would make us better in private equity,” says James. “GSO was very synergistic and complemented our other businesses well.”

The honeymoon was over quickly, though. As 2008 wore on and the credit crisis gathered steam, GSO started putting money to work. In August the group put up $1 billion in equity to buy a portfolio of busted bridge loans from Deutsche Bank, with the German bank providing 3-to-1 leverage. The approximately $4 billion portfolio was distributed across GSO’s own funds as well as Blackstone’s private equity portfolios. The next month Lehman Brothers Holdings filed for bankruptcy and all hell broke loose. Loan prices dropped 30 points, obliterating almost the entire investment — at least on paper. The Deutsche Bank portfolio was marked to about 5 cents on the dollar for the quarter ended March 31, 2009. GSO had partnered with TPG to buy a $2 billion portfolio of bridge loans from Citigroup. That also plummeted in value.

As it turned out, GSO had done thorough credit analysis and structured the debt appropriately, and it made 1.5 times its investment in two years, with every company paying off its debts. “Writing something down to zero is not your proudest moment,” Goodman says. But by the end of 2009, the firm had $24 billion in assets.

After the market bottomed in 2009, GSO launched its first rescue lending fund, which closed at $3.3 billion. The next year it acquired nine CLOs from Allied Capital Corp., and a year later it bought Harbourmaster Capital Management, a $10 billion European leveraged-loan manager, and four CLOs from Allied Irish Bank.

In its five years in the Blackstone fold, GSO has gone from having two fund products to managing 27. The breadth and scale of its funds allow it to offer a range of solutions to companies, including rescue financing and senior secured bank loans. At the same time, the platform gives it a lot of different eyes into potential investments. GSO has a view on about 1,000 companies through its CLO business, garnering leads that can be passed on to the hedge fund or other vehicles. Investments can also be shared. The Hovnanian deal was originated through the hedge fund but later expanded to include the rescue financing fund. “We stand on this very busy street corner and see all this activity,” says customized credit strategies partner Daniel Smith. Under Blackstone, GSO has the heft to write big enough checks to fully finance a solution, reducing a company’s need to find additional capital elsewhere.

GSO’s flagship hedge fund takes an activist or event-driven approach to credit. New’s team looks for companies going through some sort of upheaval, such as a covenant breach, debt maturation, regulatory change, bankruptcy or a legal dispute like MBIA’s battle with BofA. But unlike activist equity managers or “loan-to-own” credit funds, GSO doesn’t seek to change management unless something goes wrong and it has no choice. It wants to stay off the front pages of newspapers.

The firm, which has a competitive advantage by doing most of its own loan originations and investing in companies that are No. 1 or 2 in their markets, looks at about 1,000 deals every year and completes fewer than 5 percent of those. Every Monday the investment staff meets to go over ideas and review the pipeline. GSO now has offices in New York, London, Dublin and Houston.

GSO and Blackstone actively share information. Ryan Mollett, a 34-year-old managing partner who joined New’s group from BlackRock in 2011, wrote a paper late that year asserting that the housing market had bottomed. Blackstone’s real estate group saw similar evidence, and BAAM expected mortgage improvement based on results from its underlying hedge funds. As a result of the cumulative research among the different Blackstone groups, private equity bought $220 million of nonperforming residential loans, the real estate team purchased $1.4 billion of single-family homes to lease, and GSO invested in Hovnanian. At its peak, GSO had $475 million in hedge fund exposure to homebuilders and related industries and put out $600 million in financing across private market vehicles.

The Capital Solutions Fund — GSO’s rescue lending vehicle — is an object lesson in the maturation of alternative credit. In the old days highly cyclical companies in trouble could sell control to a competitor, a private equity firm or a hedge fund firm that took a loan-to-own strategy. In all cases the company would likely be giving up control at the bottom of the market. In contrast, GSO will take a minority stake, a seat on the board and a debtlike investment that pays a big double-digit coupon, but it will let management retain control. “We decided that the banking system is a mess globally, so let’s raise some money to lend to more troubled private companies that can’t tap the markets and don’t have access to the banks,” says Ostrover.

Part of GSO’s success comes from leaving some money on the table. Goodman states the obvious: “No company does business with us because we’re such nice guys, though we like to think we are. They do it because they can’t get the capital otherwise.” And many companies say GSO doesn’t scrape every penny out of a deal. “I don’t feel like I’m going to get my throat ripped out when I call GSO,” says one CEO who has done multiple deals with the company.

GSO LIKES A LITTLE, BUT NOT TOO much, market misery. Well before the downgrade of the U.S.’s credit rating in August 2011, GSO was busy preparing for the possibility that markets would freeze up if the rating agencies made good on their threats. It was keeping up-to-date in its credit work on certain companies and identifying potential situations for investment. “It’s really hard for some people to be aggressive in times of disruption because you have to do your work beforehand,” says partner Smith.

GSO put about $5 billion of capital to work as the markets slid after the downgrade. For its drawdown funds alone, it committed $3 billion to 26 companies. Its investments included City Ventures, a private homebuilder in Orange County, California, now planning to go public; EMI Music Publishing; Energy Alloys, a global provider of oil field metals; Spain’s Giant Cement Holding; and the U.K.’s Miller Group.

The firm financed Sony’s deal to buy EMI, giving the Japanese electronics maker access to a music catalog that included more than 200 songs by the Beatles. When Sony was trying to buy EMI in the fall of 2011, it couldn’t consolidate all the debt onto its balance sheet without getting downgraded. Sony went to every bank it knew, including those in Japan, but couldn’t get a $500 million bridge loan. The company initially approached Blackstone’s private equity group for a $500 million infusion of equity, but it wanted a controlling stake and Sony wasn’t about to do that. Blackstone referred Sony to GSO, which crafted a deal of mezzanine debt and equity warrants in the company.

“Many investors are quite cautious when evaluating entertainment deals — especially institutions,” says Rob Wiesenthal, then Sony’s CFO and now chief operating officer of Warner Music Group. “But the GSO team immediately understood the annuity-like cash flow streams of music publishing and how much less volatile it is than recorded music and less subject to the decline of physical recorded media.”

Wiesenthal adds that GSO was flexible enough to let billionaire David Geffen, also an investor, participate in the transaction late in the game. “David Geffen is the Warren Buffett of the entertainment industry, and they understood the value of that to the deal,” he explains. “Many investors wouldn’t know how to approach that.”

GSO also bought the debt of Clear Channel Communications, a private-equity-owned media company, and led a $1.25 billion preferred stock deal for Chesapeake Energy so that company could develop natural-gas production from shale in eastern Ohio.

Current market conditions are setting the stage for a lot of future opportunities for GSO. Annual high-yield issuance is more than double what it was in 2006 and 2007,

61 percent of bonds are trading at or above their call prices, and new issuance of covenant-lite leveraged loans in 2012 surpassed the levels seen during the credit craze in the middle of the past decade. “When the high-yield market trades at highs, we put out less capital,” says Ostrover. “As the market comes down, we put out a lot. Let’s face it, if a company can tap the public markets, they will, and they’ll get a much better deal.”

The GSO team is confident that the bright future investors are anticipating will lose its luster sooner or later, whether it’s because of inaction in Washington or rumblings from North Korea, Israel or Iran. All those covenant-lite loans will be great opportunities for GSO to step in at some point. In the meantime, it has cut back the pace of investments and is going after only the most compelling ones, in industry sectors including shipping, metals and mining, and natural gas.

GSO has $8 billion in dry powder to put to work when rates eventually rise and investors inevitably sell at least some of the bonds they’ve bought in recent years. In fact, the firm is preparing to be a buyer when rates rise and long-only mutual fund managers have to sell bonds to meet investor redemptions. Amid the froth GSO is now doing its preparatory work for the next crisis. Though investors seem to have set their concerns aside, GSO maintains that Europe poses the same risks to the global economy it always did and that rates must rise sometime in the next four years.

Patience is the key, says Smith, adding that GSO’s funds and compensation are structured in such a way that staffers don’t have to feel compelled to put money to work in deals that don’t make sense. The group has products that do better in different market environments, such as its closed-end funds and a new exchange-traded fund it recently launched with State Street Global Advisors. GSO is actively managing the leveraged-loan ETF, the first of its kind.

Europe currently offers GSO the greatest opportunities. But, as Smith says, it’s also a great place to lose money. The high-yield and leveraged-loan markets never developed there like they did in the U.S. Instead, banks dominated the leveraged-finance markets, with few institutional buyers such as high-yield mutual funds. In the U.S. banks provide about 30 percent of lending, with capital markets and investors providing the remainder. In Europe 70 to 75 percent of lending is done by banks. But that is likely to change as banks shed assets to deleverage and companies need capital. Smith calls Europe a huge opportunity — maybe a little like what Milken saw in the 1980s and DLJ in the ’90s.

But things are changing much more slowly in Europe than they did in the U.S. Every European country has its own business climate, union rules and regulatory system, and bankruptcy law isn’t always clear enough for a manager like GSO to get the assurance it needs to invest in a troubled company. Even so, GSO has 31 investment professionals in London, and they are doing more deals now than the firm is doing in the U.S.

Nearly five full years after the worst of the financial crisis, the real estate market is finally on the mend, investors are wondering if homebuilders’ stocks have rallied too far, and the outlines of the new order of Wall Street are coming into sharper focus. The defanged banks are receding into the background and making peace with new regulations designed to emasculate their balance sheets. The new power brokers in the financial industry are money managers and investors like GSO, which control real assets.

“There is a wealth transfer going on from banks’ shareholders to the investors in our funds,” says Goodman.