The 2008 financial crisis has changed the U.S. economy in deep and enduring ways. Now that we are more than five years out from the start of the crisis, it’s the right time to make an assessment: Where is the world’s largest economy in its recovery, and what have been the long-term effects of the crisis? These questions are particularly important to reflect upon now that U.S. equity prices are hitting record highs. Is the sentiment justified?

On the one hand, there are many reasons to be optimistic about the recovery. I point to three. The first is the quick repairing of the U.S. banking system. The Troubled Asset Relief Program, or TARP, bailouts, though controversial, helped stave off a Great Depression scenario of full-on banking collapse. That was a key challenge in Japan after its financial crisis and continues to be the case in Europe, where many banks remain undercapitalized. This intervention very quickly allowed the arteries of the financial and real economy to resume operating — albeit at a much reduced pace — after the initial shocks of late 2008.

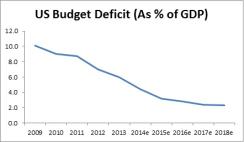

The second reason is the shrinking federal budget deficit. Despite the cries of various commentators and analysts, the U.S. budget deficit has decreased from $1.4 trillion in 2009 to $680 billion in 2013, with Congressional Budget Office projections predicting a further decrease in 2014 to $560 billion and in 2015 to $378 billion. The shrinking deficit can be explained by improved fiscal federal revenues, significant cuts in government expenses and strong growth since 2009.

Source: White House Office of Management and Budget

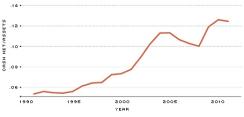

The third reason to be optimistic is corporate balance sheets. By and large, U.S. corporations have retained healthy balance sheets in the aftermath of the crisis, providing significant opportunity for investment as confidence is restored. Add to this a shrinking trade deficit, a slow clawback in housing prices and an oil boom, and you have the makings of a buoyant recovery.

Source: Compustat/Ritzholtz

Equity investors have taken the above news to heart. With interest rates still very low, we have started to see a reversal of flows back into equity markets with a bias toward the U.S., particularly as Europe continues to stagnate and emerging markets face obstacles of their own.

But not so fast. Despite these reasons for optimism, I believe that many participants are still living in a quantitative easing–induced euphoria that has masked the many structural challenges in the U.S. economy. These issues may very soon have an impact on corporate earnings and the nation’s long-term fiscal sustainability. Below, I highlight what concerns me most about the recovery.

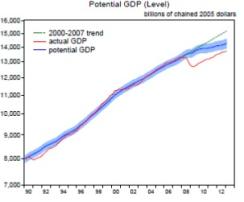

The first is that the crisis may have caused significant long-term damage to the productive capacity of the U.S. economy, or hysteresis, as David Wilcox, director of the Division of Research and Statistics at the Federal Reserve Board, described in his paper presented at the International Monetary Fund annual conference held in November. Such damage could be the result of labor stagnation, lack of capital deepening and the erosion of multifactor productivity during the past five years. Wilcox estimates the reduction in potential gross domestic product could be as high as 7 percent, or $1 trillion. The potential reduction in output may have significant implications for what the end point of the U.S. recovery could mean — a scenario that I believe is underappreciated by market participants. In other words, the growth trajectory of the U.S. could potentially be significantly lower than expectations prior to the 2008 financial crisis, which would have many knock-on effects on labor markets and corporate profits.

Source: Reifschneider, Wascher and Wilcox, IMF

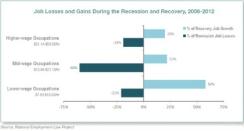

The second concern is the deeply wounded labor market. The total labor force participation rate was 62.8 percent in October, down from 66.1 percent in October 2003 and the lowest level since 1978. The rebound in GDP has not been matched by a quality labor recovery, with some estimates showing that the approximately 58 percent of jobs created since 2010 have been categorized as low wage.

Source: National Employment Law Project

With significant deleveraging happening at the household level, a poor labor market could translate into a prolonged period of inadequate demand. That would have all sorts of implications for U.S. monetary policy (a potentially longer period of easy money) and for U.S. fiscal policy (decreased tax collection, increased unemployment benefits and other safety-net provisions). Some economists, such as Paul Krugman and Larry Summers, have recently argued that we could be entering a period of "secular stagnation" as a result of these challenges. If they are right, the implications could be daunting for the U.S.

The third concern — perhaps the most significant — is whether the U.S. economy is resilient enough to face the next shock, be that a crisis of the U.S. domestic economy, the Chinese banking sector or in emerging-markets sovereign debt. When economies enter downturns, the starting point matters. The fundamentals of the U.S. economy — employment, housing, consumer confidence and political trust — remain very weak. The fragility of the U.S. and other developed-market economies needs to be priced in as investors look toward the medium term.

The discussion on the U.S. economy has become too narrowly focused on monthly jobs numbers, which is wrongheaded. The 2008 financial crisis has accentuated, and in some ways created, deep structural problems that no amount of quantitative easing can fix. Instead, the way forward is to address these economic issues, from inadequate public infrastructure to an improved and cheaper health care system to job-training and employment programs, on a major scale.

Aniket Shah is an investment specialist with the Investec Investment Institute, part of Investec Asset Management. Along with Joe Colombano, economic adviser in the executive office of the secretary-general of the United Nations, he co-edited Learning from the World: New Ideas to Redevelop America, a book to be released November 29 by Palgrave Macmillan.